In Part I of this series I suggested that you should see progress in your exercise routine. Further, I broached the idea that muscular strength and muscular size are not necessarily the same. Finally, I argued that getting “too big” is nearly impossible for you to do. This is Part II of the conversation.

Big vs. strong. What’s the difference?

Muscle bulk is what a lot of men (especially young guys) want from their exercise program. For many of you though, your fitness goals don’t include bulking up. Most women I encounter want to get leaner and essentially smaller. Obesity is a big problem in America so many of us definitely don’t need to consider enlarging ourselves. Endurance athletes don’t need to haul around extra muscle as it can hinder performance. Because of all this we see a lot of people lifting rather light weights for very high reps (15-20 or more). The problem is, you can’t actually get stronger this way.

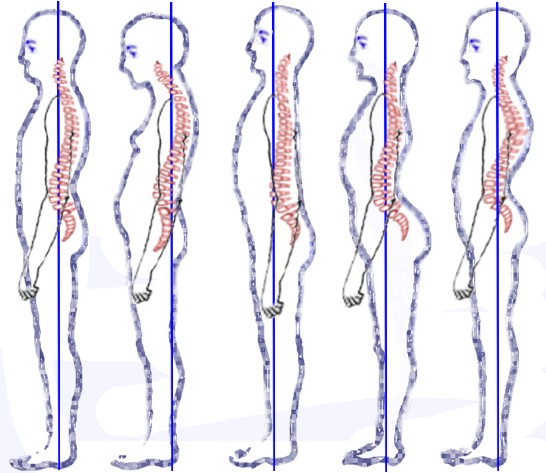

Let me offer this thought to you: You can get stronger–without getting bigger! You can learn to create more force with your muscles without much if any additional muscle growth. The two circumstances are not the same. Strictly speaking, bigger muscles can be stronger than smaller muscles, but strength is much more than that. Strength is also very much the result of changes within the central nervous system (CNS). Here’s more on that.

Neurology of strength

It’s helpful to understand a little bit about processes by which we get stronger. Besides some potential muscle growth, what happens when we strength train? Without getting overly science-y, here’s a description:

-

Better intramuscular coordination:

This is learning to use more of an individual muscle. Muscles are made up of muscle fibers. Those muscle fibers are innervated (“fired”) by nerves. The nerve plus the muscle fibers it innervates is known as a motor unit. Untrained individuals can recruit only so many motor units for a given task. Effective strength training enables us to recruit more motor units within an individual muscle.Strength training also changes the rate at which our motor units fire. Untrained people fire their motor units more slowly than trained people. Proper strength training can enable us to fire our motor units very quickly. The result is we can be stronger and/or faster and muscle growth is unaffected.

At the same time, strength training also teaches us to synchronize these motor units to fire together. All of this is skill, and it has nothing to do with muscle growth.

-

Better intermuscular coordination:

This is better coordination of muscle groups. In looking at almost any common human movement (sitting to standing, running, reaching, pushing, pulling, lifting something off the ground, climbing stairs, etc.) multiple body parts move together. Proper exercise selection (multi-joint exercises like squats, lunges, rows, presses, etc.) plus appropriate loading of these exercises enable us to develop stronger movement patterns rather than just a stronger quad, calf, bicep, etc. This again is a way of becoming stronger without enlarging the muscles. -

What else?

Effective strength training gives us stronger connective tissue. Ligaments and tendons become stronger just like the muscles. Our bones also get stronger if we load them effectively. A good strength program is a very effective way to protect against injury and increase bone density in people of all ages and abilities.

Examples of Stronger, Not Bigger

The majority of sports actually don’t require athletes to be particularly big. American football linemen need to be big in order to

shove opponents out of the way. It’s a similar situation with sumo wrestlers. Shot putters need to be big so they can put a lot of mass against the shot. Beyond that, very large athletes are often at a disadvantage. They can’t generate as much power relative to their body weight. They can’t endure as well. Thus, for many athletes, some degree of increased muscle mass may be a good thing, but being “too big” is not an advantage. Strength however is always in demand.

Most sports involve sprinting of some sort. More strength helps an athlete sprint faster. Does more bulk help? Only up to a point. A massively muscle-bound body doesn’t help.

Weight class athletes such as boxers, weightlifters, martial artists, and wrestlers must stay within a certain weight range to compete. Now, we’ve all seen the stereotypical massive superheavyweight weightlifter or powerlifter. Look at the lighter weight classes of these sports though and you won’t see such hulking physiques. You’ll see lean, strong athletic physiques. These people are always looking to get stronger and more powerful without getting bigger.

Gymnasts are excellent examples of athletes who must be very strong and

powerful yet clearly don’t benefit much at all from enormous amounts of muscle bulk. Have you ever seen a gymnast that was “too big?”

So there are numerous examples of people who require great strength but have no need of excessive muscle. How exactly do they get there? I’m glad you asked! Stay tuned for Part III of this series.