I’m fortunate to be able to run in the Rocky Mountains. Every trail run features ascents and descents that are often long and/or steep which means significant changes in pace. I often run with a group and I’ve noticed that it’s not uncommon for runners to run too hard on the ascents. It’s easy to hit the redline on ascents, to burn out, and have the run reduced to a stagger. (Sometimes I’m the one running too hard.) This isn’t optimal for racing or training. Running harder isn’t always better.

Check the ego

“I’m a runner! Therefore I must run!”

I’m probably not the only runner who feels self-imposed pressure to by god keep running! Walking can feel like an embarrassing moral failure, especially when running with a group. I want to compete and keep up with my peers. In this case, my brain, wired to prefer short-term rewards over long-term goals, works against me. A simple question illuminates the right course of action:

What’s the goal?

Is my goal to “win” a training run of no consequence? Or is it to train effectively for a specific race? The answer is the latter. Put another way, the purpose of a training run is not to prove fitness, but to improve fitness.

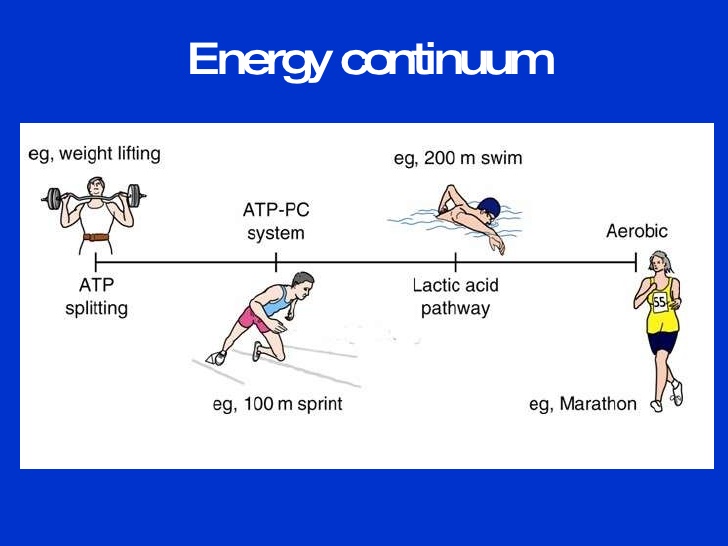

In my case, I’m training for long trail races. That means low-intensity running and hiking for a long duration. Thus I need to train my aerobic energy system, not my phosphocreatine or glycolytic systems. The goal for long training runs is to build a bigger aerobic engine. If I run too hard, drive my heart rate too high, and generate too many hydrogen ions (Neither lactate nor lactic acid is responsible for burning muscle. It’s a buildup of H2 ions. The myth must die!) then aerobic conditioning is deemphasized. I’m training wrong and impeding my goal if I do that.

(There is a time and place for hard running. The training plan may call for harder efforts: hill intervals for instance. That’s a different topic.)

What I think I’ve learned

At some point walking up a slope is more economical than running. Running economy matters more as races go longer. For a short race, running up a steep hill may be fine because I’m not limited by energy reserves, but for long races, conserving energy matters a lot.

Research from CU Boulder has investigated running vs walking up a range of slopes. One of the researchers, Nicola Giovanelli, Ph.D., discussed the research on the Science of Ultra podcast. He suggests that walking makes sense on slopes starting at about 15-20 degrees.

Running coach David Roche offers further analysis in this article at TrailRunner.com:

“The study found that ‘on inclines steeper than 15.8°, athletes can reduce their energy expenditure by walking rather than running.'”

“While that study looked at relatively fresh athletes, it’s likely that the optimal grade for walking decreases as the length of the race increases and muscles fatigue. In long ultras, like 50- and 100-milers, most racers are hiking on anything over eight to 10 percent later in the race—grades they’d usually bound up. So if you are doing a short race with steeps or a long race with normal hills, knowing how to walk can save energy. Here are three form tips to unlock your hiking prowess.”

Walk early. Walk often.

For my purposes, I’ve translated the research into this: Walk early. Walk often. I start walking/power hiking well before I blow up. I stop running and start hiking before I truly need to start hiking. I start before the slope gets very steep. This is similar to efficient uphill cycling in that a rider should shift into a low gear early and before he or she struggles at a very low cadence.

I find that I can keep pace with and often pass other runners when I hike instead of run. They work harder yet we move at about the same rate. The ascent often resembles a slinky type of process where we pass each other a few times before we hit the peak. Often, the other harder working runners are completely gassed at the top while I can resume running.

Low-end speed

I’m not an elite-level runner, so there’s no question that I will spend significant time hiking and walking during my races, especially during the 40-mile Grand Traverse Run. Therefore my training should resemble the race. If I prioritize my low-end speed, get faster at going slower, then that should help my performance more than developing higher-end speed.