A few weeks ago I had a very interesting experience regarding my ACL rehabilitation. It’s very similar to an experience I had with Achilles tendon and heel pain. Here it is.

A perceived setback

I had ACL reconstruction on May 1, 2014. I have been very aggressive with my rehabilitation and I felt it was going very well. My PT and I agreed on a strategy and he approved of the process in general. I knew that sitting and resting was not the right way to go if I wanted to regain full function. For people like me, laziness wasn’t a problem; an overly aggressive approach might be though.

I knew that I could be in trouble if I did too much work too fast and stressed the knee too much. I worried that I’d drifted into this territory when at almost nine months I experienced more pain than I expected. I had a final appointment with my surgeon and she expressed some concern at my symptoms. We agreed that I should back off my activity and rest a bit. Seems perhaps I had reached the point of “too much of a good thing.”

I backed off lifting, running a cycling. I didn’t stop my activity completely but I cut it back significantly. After a couple of weeks I realized the knee wasn’t feeling much better. I continued to experience frequent pain; not debilitating but somewhat worrisome. I decided a visit to the PT was in order. I wanted to get some guidance and make sure I hadn’t damaged the graft.

The long and the short of the visit was this: The graft and my knee were fine. I needed more strength in the leg and around the knee. I needed to do more work, not less! Eureka! (My previous PT had moved on to another position and I had to meet with a new one. Unfortunately, the “bedside manner” of this PT left much to be desired. Right off the bat she was rude, dismissive and she interrupted my answers to her questions. I became very frustrated and it was work to keep my yapper shut and listen to what I needed to. Fortunately I got the information I needed.)

From here, I was ready to rock ‘n’ roll.

Goodbye fear. Hello confidence!

My experience was a very clear experience of what modern pain science has been finding recently. Here are some important points:

1) Pain doesn’t equal injury: In Reconceptualising Pain According to Modern Pain Science, neuroscience researcher Dr. Lorimer Moseley has made several points about pain. Two are pertinent here:

- pain does not provide a measure of the state of the tissues

- The relationship between pain and the state of the tissues becomes weaker as pain persists.

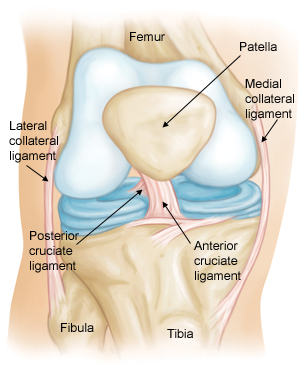

Yes I had an injured knee and yes I had surgery in which part of my patellar tendon was cut out in order to make a new ACL. This was all very disruptive to parts of the knee and was clearly part of the pain I was feeling. It takes about six weeks for the graft to heal. The reconstructed ACL is pretty much healed at six months which would’ve been October for me. In other words, my knee was/is healed and any pain wasn’t from tissue damage.

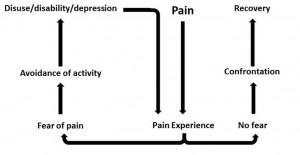

2) Fear is a significant obstacle that must be addressed: Fear is a powerful part of our pain. Overcoming that fear is major part of a successful rehab and return to activity. The pain in my knee caused me to worry that I’d re-injured it and it led me to avoid a lot of activity that I enjoyed. This condition is known as fear-avoidance. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) describes fear-avoidance this way:

Psychological factors play a key role in the development of chronic musculoskeletal pain, in particular dysfunctional beliefs about pain and fear of pain. Fear of pain leads to avoidance of activities (physical, social, and professional) that patients associate with the occurrence or exacerbation of pain, even after they may have physically recovered. Whereas this response is adaptive in the acute phase—rest promotes recovery—it leads to disability and distress when avoidance behavior is continued after the injury has healed.

“Fear-avoidance model” by LittleT889 – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fear-avoidance_model.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Fear-avoidance_model.jpg

When I learned that my parts were solid and strong and that I wasn’t broken, I felt the fear drain away like water down a toilet. I was a happy dude!

Another of Moseley’s points is important here: that pain can be conceptualised as a conscious correlate of the implicit perception that tissue is in danger.

Big words. What does that statement mean? I’ll let Moseley explain (emphasis is mine):

“First, there are other central nervous system outputs that occur when tissue is perceived to be under threat, and second, that it is the implicit perception of threat that determines the outputs, not the state of the tissues, nor the actual threat to the tissues.“

In even simpler terms, we may feel pain absent any damage but we feel pain when our brain perceives a threat–even when there is no threat. I compare this to a car alarm that is set off by the wind. There’s no break-in occurring yet the alarm signal is going off due to the alarm sensing a threat.

3) Patient education is vital: Very interestingly, an effective strategy in treating chronic pain is patient education. This strategy of patient education is supported in several studies that are discussed in a review in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and it’s further discussed in an article titled Can Pain Neuroscience Education Improve Endogenous Pain Inhibition? Literally, knowledge of pain processes can reduce pain. (Pain is weird!) I believe that my experience supports this phenomena.

(To be clear, it’s not that I received education on how pain works. I received the message that my knee was solid, not injured and that it could be worked very hard.)

Keep this in mind.

Dr. Moseley discusses pain education in Pain really is in the mind, but not in the way that you think. I like what he says here:

“The idea that an inaccurate understanding of chronic pain increases chronic pain begs the question – what happens if we correct that inaccurate piece of knowledge?

We’ve been researching the answer to this for over a decade, and here’s some of what we’ve found:

(i) Pain and disability reduce, not by much and not very quickly but they do;

(ii) Activity-based treatments have better effects;

(iii) Flare-ups reduce in their frequency and magnitude;

(iv) Long-term outcomes of activity-based treatments are vast improvements.”

Most of us outside the medical community probably still equate pain to damage. Many inside the medical community still think that way too. (Blame Rene Descartes.) We now know better. Rather than address pain from a strictly biomechanical approach, therapists would be well advised to study and adopt what’s known as the biopsychosocial model for pain. This model is explained very well here and discussed in-depth here. We patients will be well armed in a fight against pain if we understand this model too.