This post is mostly the same as my recent article in CompetitorRunning.com. I discuss several exercises in the article designed to help runners overcome common painful issues related to running. For this post, I include pics and videos of the exercises. Here it is.

Pain Science for Runners

Acute vs Chronic Pain

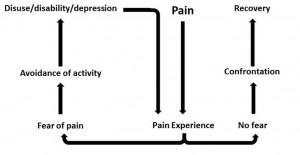

Chronic pain is frustrating. Painful feet, ankles, knees, hips, and low-backs are common in runners. Chronic pain may bring fear that you’re broken, weak, and fragile. Thus you avoid many meaningful activities. You may obsess over your pain. This is the fear-avoidance cycle and it fuels itself.

Chronic pain is different from the pain of an acute injury such as a bone fracture; dislocation; or a cut, scrape, burn, or puncture. Chronic pain lasts long after an acute injury has healed.

Pain serves a valuable purpose but with chronic pain, the pain remains after it has served its purpose. Chronic pain comes from a “broken pain system,” akin to a car alarm that goes off for no reason. Fortunately, you can overcome chronic pain and start running again.

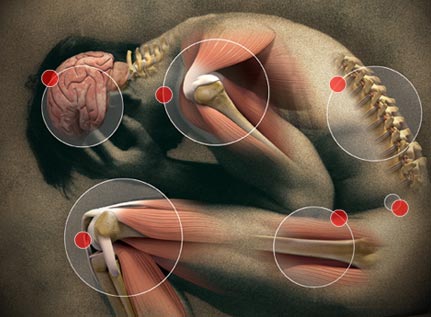

Pain science reveals several important points regarding chronic pain. Most important is that pain rarely equals harm or damage. You can be hurt and strong at the same time. (You can also have damage with no pain. Ever find a bruise but have no memory of how it got there?) Chronic pain is the result of a sensitized nervous system aka central sensitization (http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/understanding-chronic-pain/what-is-chronic-pain/central-sensitization). Contributors to sensitization include:

- Beliefs such as you’re broken and further activity (running) will break you more.

- Lifestyle factors: job stress, relationship stress, lack of sleep, poor diet, lack of exercise

- Coping strategies: Avoiding running out of fear which drives you deeper into despair and further sensitization.

- Emotions: catastrophizing, fear, anxiety, anger, rumination

- Tissue stress: Tissue stress can definitely contribute to pain. Remember though, tissue damage is typically a minor contributor to sensitization.

All of the above factors may be kindling for a pain fire. One too many stressors may spark the fire. You feel pain when the accumulation of stress exceeds your brain’s perceived ability to cope. There are two ways to tackle pain. One way is to decrease the stress that contributes to pain. Another way is to increase your resilience and get strong.

Confront your pain

You can lower nervous system sensitization in several ways:

-

- General physical activity

- Talk with a counselor

- Various therapeutic techniques: massage, foam rolling, manual therapy, hot, cold

- Consistent sleep schedule

- Improve your diet

- Load and strengthen the place that hurts.

- Resume running

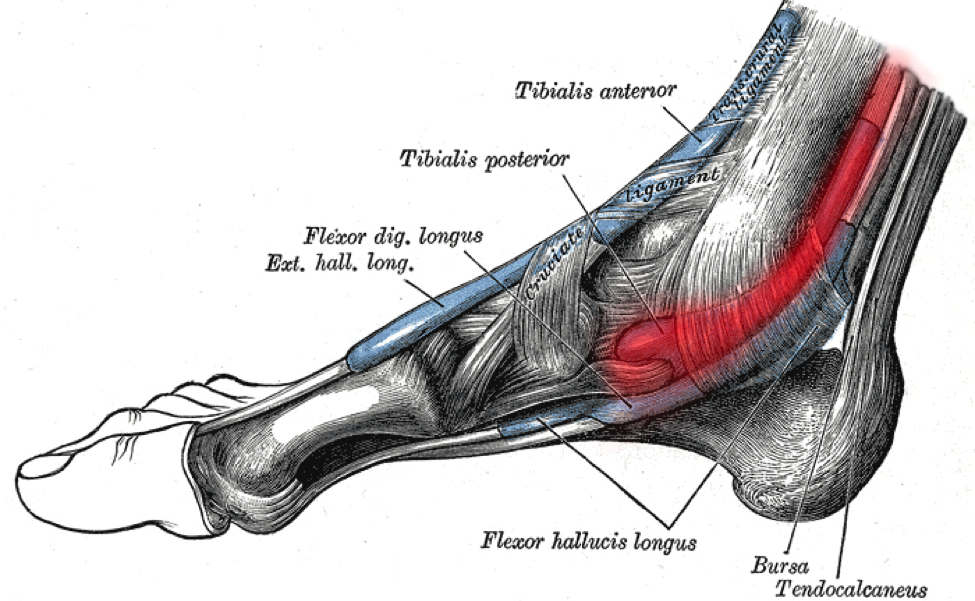

Your bones, connective tissue, joints, and muscles are very strong and they respond well to loading. If you’ve been guarding and resting part of your body then it gets weaker. Structures like the Achilles and patellar tendons need strength, not more rest. Physiotherapist, chiropractor and pain expert Greg Lehman favors gradual strengthening as one of the best ways to reduce pain.

Get strong – Load it!

Loading strengthens muscles and connective tissue while and provides an analgesic effect. Physical activity boosts your mood, builds self-efficacy, and shows that you’re not broken. By engaging in exercise you break the fear-avoidance cycle. Here are several exercises to help with several conditions. A comprehensive guide is beyond the scope of this article.

Isometrics:

Isometrics work well to calm pain. Contract and hold with no motion for 30-60 seconds. Perform isometrics frequently throughout the day.

- Right: Heel raise loaded with a kettlebell for Achilles and plantar

Heel raise

fascia pain. Use a bent or straight knee.

- Below: Wall sit for patellar pain. Progress from two to one leg.

Wall sit

- Below: Straight-leg bridge for glute/hamstring pain. Progress from two to one leg.

Straight-leg bridge

HSR (Heavy Slow Resistance) training:

Exercises should be exhausting in 5-10 slow, deliberate reps. (Most of these can also be done as isometrics too.) Start with bodyweight then add weight via barbells, dumbbells, kettlebells, weight vests, machines, or rubber tubing/bands. Persist into pain no higher than a 4 on a 1-10 scale.

Heel raises for Achilles tendonitis can be done with a straight or bent knee.

Loading the knee and hip reduces knee pain.

Band knee & hip extension

Band walks

Side bridges target abs and hip

Band leg press (A squat can be done in a similar way.)

IT Band syndrome

1-leg squat

1-leg bridge

Band leg press (A squat can be done in a similar way.)

Resume activity

Exercise is medicine. If you’ve avoided running for a while then it’s time to run! A little bit of running will help you understand that you’re not broken and the physical activity will help calm your nervous system. You’ll use the process of graded exposure. Add work gradually, keep pain at a minimum, and you’ll increase your capacity for activity.

Try a run/walk protocol like this:

- Week 1: 1 min. run/3 min. walk, repeat 10x

- Week 2: 2 min. run/2 min. walk, repeat 10x

- Week 3: 3 min. run/1 min. walk, repeat 10x

- Week 4: 40 min. run

Perform each workout twice per week on non-consecutive days. Pain should be no higher than a 4 on a 10-scale (1 = no pain, 10 = very painful) and pain should not alter your running form. Don’t push through severe pain.

Flare-ups

It’s not uncommon for pain to flare up after activity. Don’t be alarmed. You haven’t done more damage. You’ve pushed a boundary and your nervous system has overreacted. Reduce your activity level a little bit next time you exercise.

Finally

You may need more information beyond this article. A physical therapist or other medical professionals can help guide you through recovery. Injuries such as stress fractures definitely need to be unloaded and rested. If your pain gets worse with activity then seek medical care.

while running:

while running: