For effective management of persistent pain, provide a clear understanding of the factors that drive pain, develop graduated strategies to normalise and optimise movement patterns while controlling pain, and couple these steps by prescribing sports specific conditioning and a graduated return to sport. Addressing psycho-social stressors and unhealthy lifestyle factors is part of this process, especially where ‘central’ pain features are dominant. Magic bullets don’t exist, so don’t promise them.

– Dr Peter O’Sullivan, Curtin University, West Australia

Tiger Woods received a lot of coverage earlier this month for withdrawing from a golf tournament due to back pain. Tiger mentioned back spasms in interviews and made the following statement:

“It was a different pain than what I had been experiencing, so I knew it wasn’t the site of the surgery. It was different and obviously it was just the sacrum,” Woods said. “The treatments have been fantastic. Once the bone was put back in the spasms went away, and from there I started getting some range of motion. My physio is here. If it does go out (again), he’s able to fix it.”

So the implication here is that the sacrum can in fact pop out and be put back in place. And that once the sacrum is back where it belongs–presto!–the pain was gone. This is the type of statement that perks up the ears of numerous therapists, coaches and trainers. This is also the type of information that grabs the attention of multitudes of back-pain sufferers. There’s hope! A magic treatment is at hand!

First, can a sacrum pop out? For that question, I like these words from UK physiotherapist Adam Meakins aka the Sports Physio:

“The notion of anyone’s sacrum just ‘popping out’ is complete and utter nonsense, let alone the sacrum of a fit athletic professional male golfer without any past risk factors or history of significant trauma…

SACRUMS DONT JUST POP IN AND OUT…

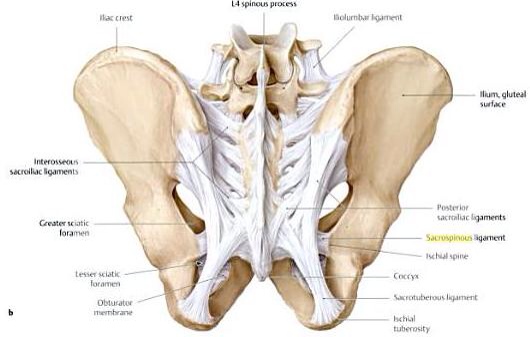

All that white webbing-type stuff are ligaments. Very strong stuff. The sacrum is underneath it between the hip bones at the bottom of the spine.

For starters the pelvis is an incredibly strong and stable structure with many, many strong ligaments and muscles across it. The sacroiliac joint does have some small amount of movement, and yes some have more or less than others, but the variation is minimal and the ridiculous belief that many therapists have in thinking that they can 1) feel this joint move 2) decide if it’s in the right or wrong position and 3) adjust it with manipulations is just again complete and utter nonsense based in pseudo science and nothing more than palpation pareidolia as I have discussed before in my previous blog here and on the assessment of the painful SIJ here and its management here.”

So why did Tiger think his sacrum had ‘popped out’ well there are two possible reasons.”

One very competent and observant trainer is Boulder’s Mike Terborg. He sent me an informative article from the British Medical Journal Blogs called Common misconceptions about back pain in sport: Tiger Woods’ case brings 5 fundamental questions into sharp focus. It was written by physiotherapist Dr. Peter O’Sullivan. I won’t go into every detail of the article but I’ll summarize the big pieces. (Emphasis is mine.) O’Sullivan lists five quotes related to Tiger’s pain and then asks questions of those observations. He cites research to support his answers. Go to the article to read the whole shebangabang.

- “Tiger has a pinched nerve in his back causing his pain.”

What is the role of imaging for the diagnosis of back pain? O’Sullivan: “Disc degeneration, disc bulges, annular tears and prolapses are highly prevalent in pain free populations, are not strongly predictive of future low back pain and correlate poorly with levels of pain and disability. (Deyo 2002, Jarvik JG 2005).” - “Tiger had a micro-discectomy for a pinched nerve which had lasted for several months.”

What is the role of microdiscectomy for the management of back pain?

O’Sullivan: “The role of decompressive surgery (micro-discectomy) should be limited to nerve root pain associated with progressive neurological loss (e.g., leg weakness)… (O’Sullivan and Lin 2014). Micro-discectomy is not a treatment for back pain.”

- “My sacrum was out of place and was put back in by the physio.”

What role do manual therapies play to treat back pain?O’Sullivan: “Passive manual therapies can provide short-term pain relief. Beliefs such as ‘your sacrum, pelvis or back is out place’ are common among many clinicians.

These beliefs can increase fear, anxiety and hypervigilance that the person has something structurally wrong that they have no control over, resulting in dependence on passive therapies for pain relief (possibly good for business, but not for health). These clinical beliefs are often based on highly complex clinical algorithms associated with the use of poorly validated and unreliable clinical tests (O’Sullivan and Beales 2007). Apparent ‘asymmetries’ and associated clinical signs relate to motor control changes secondary to sensitised lumbo-pelvic structures, not to bones being out of place (Palsson, Hirata et al. 2014). In contrast, there is strong evidence that movements of the sacroiliac joint is associated with minute movements, which are barely measurable with the best imaging techniques let alone manual palpation (Kibsgård, Røise et al. 2014).”

- “I need to strengthen my core to get back to playing golf again.”

What is the role of core stability training?

O’Sullivan: “’Working the core’” has become a huge focus of rehabilitation of athletes and non athletes in recent years.

Recent studies have also demonstrated that positive outcomes associated with stabilisation training are best predicted by reductions in catastrophising rather than changes in muscle patterning (Mannion, Caporaso et al. 2012), highlighting that non-specific factors such as therapeutic alliance and therapist confidence may be the active ingredient in the treatment – rather than the desired change in muscle.“

- What should clinicians do? The paradigm shift required for managing a complex multidimensional problem like back pain.

O’Sullivan: “Firstly, clinicians need to realise that back pain does not mean that spinal structures are damaged – it means that the structures are sensitised…There is growing evidence that low back pain is associated with a combination of genetic, pathoanatomical, physical, neurophysiological, lifestyle, cognitive and psychosocial factors for each domain. The presence and dominance of these factors varies for each person, leading to a vicious cycle of tissue sensitisation, abnormal movement patterns, distress and disability (O’Sullivan 2012, Rabey, Beales et al. 2014).”

O’Sullivan makes these recommendations to clinicians:

To adopt this new approach clinicians require at least two things:

- Change of mindset: Abandon old unhelpful biomedical beliefs, and embrace the evidence to change the narrative to help people with pain understand the underlying mechanisms linked to their disorder.

- New and broader skills for examining the multiple dimensions known to drive pain, disability and distress. These assessment skills need to be complemented by the skill of developing innovative interventions that enhance self management, allow the patient to engage in relaxed normal movement. The clinician also needs to encourage the patient to adopt healthy lifestyles and positive thinking about backs (O’Sullivan 2012).

The change he advocates for is sloooowly happening in some areas of health care. The strictly biomechanical model (pain = injury) is still king.