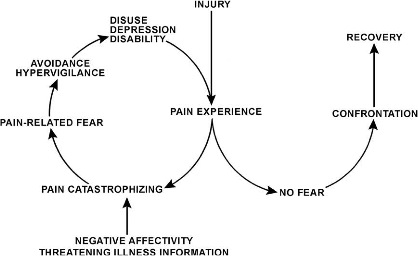

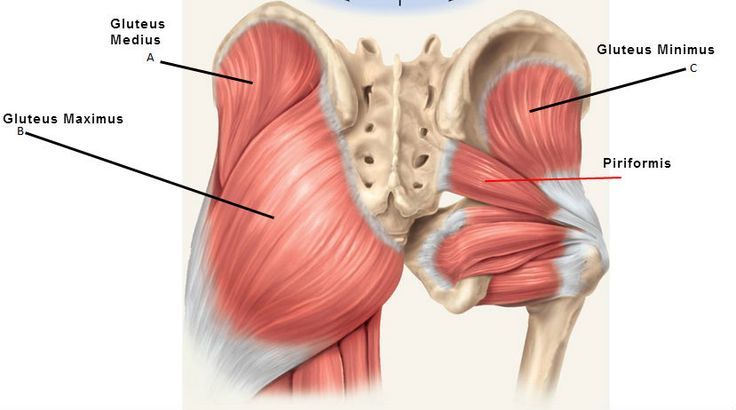

I’ve had a lightbulb moment thanks to an Instagram post by Brett “the Glute Guy” Contreras, PhD. (I wish I’d saved the post. Now I can’t find it… Oh well.) He described training the glutes in both a linear and rotational fashion. This makes sense when considering the alignment of the muscle fibers of the glute muscles with the glute max being the best example. The fibers are diagonal which means they can exert force both both in a straight line and in rotation.

The gluteus maximus fibers facilitate both sagittal plane and transverse plane movement.

I’ve long used exercises that train the glutes linearly: squats, lunges, and deadlifts for example. And now I recognize that I’ve only scratched the surface or paid lip service to the rotational ability of the glutes. I’ve gained a new appreciation for some exercises that long avoided, such as the clamshell.

I’ve been doing more clamshells in my own workouts to help address some of the faulty foot mechanics that led to some recent toe pain. The glutes play a powerful role in controlling how the feet move and I believe clamshells and other rotational glute exercises have helped me.

Linear exercises

- Deadlift, 1- and 2-legged

- Squats, 1- and 2-legged (1-legged squat)

- Romanian deadlift, 1- and 2-legged (Video 5 is a 1-leg RDL)

- Kettlebell swings (Video 8)

- Bridges

- Barbell hip thrusts (Video 1)

- Most lunges and split-squats

- Forward step-ups

- Good mornings (video 6)

- Single-leg tube squat with the tube attached straight ahead

- Sprints

Rotational exercises

- Clamshells

- Lateral band walks

- Hip airplanes

- Lunges with rotation

- Single-leg tube rotation

Anti-rotation exercises

These exercises impose a load on the body that will try to rotate you. Your job is to resist the rotational forces. These are really whole-body exercises but the glutes are definitely involved.

- Anti-rotation squat

- Anti-rotation split squat (video 3)

- Single-leg tube squat with the tube attached to the side

- Offset Romanian deadlifts (video 4)

Exercise wisdom

In almost 20 years of training, I’ve thrown many babies out with some bathwater. I’ve fallen for dogma and rejected certain exercises because I thought they weren’t “functional” or had no carryover to life outside the gym. The clamshell exercise is one example. Who needs to have strong hips while lying down sideways? What use is that, especially to athletes?

It’s a relief to discover that very smart exercise professionals have had a similar experience. Physiotherpist, chiropractor, and pain expert Greg Lehman said this about the clamshell as it pertained to runners:

“I used to abhor the clamshell. Then I started testing more runners with the clamshell. A number who tested strong in many positions would tremble during the clamshell. Crazy, they had a lovely one leg squat, strong hip abduction but had trouble with 10 or 15 clamshells. What does that tell me? Such a massive deficit in function. Would you suggest clamshells here or something to address that specific movement? This seems like a case where I would suggest clamshells. If a runner can’t do them I would want to address that deficit.

“But, do I want to see every runner doing them as part of a ‘functional’ program. Of course not. They suck for that. This is a case where the exercise prescription is ‘functional’ because it addresses a specific limitation in a specific runner.”

The clamshell is also recommended by physical therapist, and running/cycling coach Jay Dicharry.

I’ve returned to various exercises with a new appreciation. I hope that as I age and gain experience that I also gain wisdom. I must remember to maintain some skepticism about just about everything. At the same time, I should be willing to revisit what I think I know and reevaluate my thoughts.