Several articles have grabbed my attention. One is a concise summary of the current understanding of pain. Another discusses breakfast and the flimsy evidence supporting its importance. Next, science looks at the efficacy of reducing carbs vs fats for weight loss. Finally, drinking eight glasses of water a day is based on nothing.

Pain and lifting

The issue of pain is a continual theme in this blog. I’ve dealt with periodic bouts of lingering pain. The upside to this is that I’ve learned a lot about pain. Whether we’re an athlete or not, most of us will encounter non-acute or chronic pain.

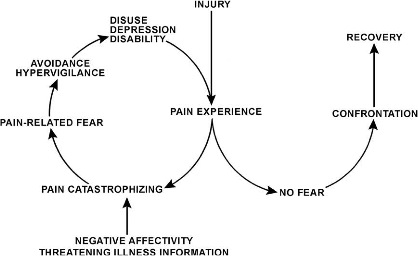

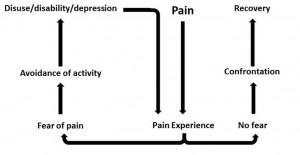

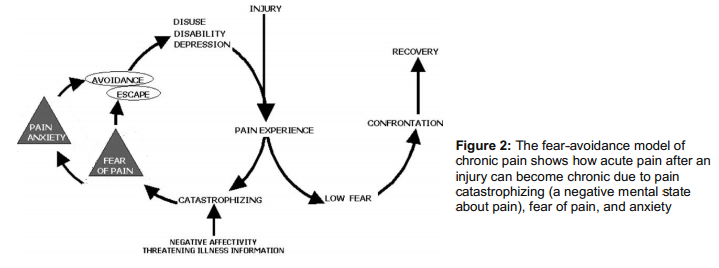

It can be scary and depressing to us especially if it limits our ability to train. Interestingly, learning about how pain works can actually help us feel better (low-back pain in this case). Pain is NOT simply an indication of tissue damage. It’s very much a product of the brain. How we perceive our bodies (damaged or strong), our pain (threatening and scary or just a nuisance) and our expectations (“I’m broken and ruined,” or “I’ll be fine.”) are major influences on the pain process.

In that direction, Elitefts.com has a worthwhile article called 3 Things Lifters and Coaches Need to Know About Pain. It’s concise and fairly easy to understand for non-scientists. I think this information is useful for coaches and trainers who will certainly come across an athlete or client in pain. It may also prove helpful to you if you’re in pain. Here is a summary:

1. You are not your MRI or your X-Ray. Many people have tissue damage or degeneration on imaging but walk around without pain everyday. If you’re dealing with pain or an injury, get a thorough medical history and functional examination done by a qualified health professional, preferably one that works with athletes and lifters (they are out there).

2. Understand that pain (particularly chronic pain) isn’t purely related to biomechanics or injury. Biological and psychosocial factors both contribute to a person’s pain experience.

3. When working with clients, don’t create fear or a nocebo effect by berating your clients on their lifting technique, posture, or movement capabilities. Instead, work through your client’s issues with positive coaching and cueing to build a great training effect.

Read the article to get more detail.

Breakfast and weight loss

“Breakfast is the most important meal of the day.”

You’ve heard it. You believe. I’ve preached it to clients. It seems the earth rotates around this statement. But, is this bit of gospel based on anything of substance? Not really.

In The science of skipping breakfast: How government nutritionists may have gotten it wrong the Washington Post discusses research that shows the following:

“In overweight individuals, skipping breakfast daily for 4 weeks leads to a reduction in body weight,” the researchers from Columbia University concluded in a paper published last year.”

Another golden idol knocked from its pedestal! How can this be? Why would the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans tell us something that isn’t supported by good evidence?

The Post article does a good job of discussing the answer.

One of the key pieces of evidence, for example, examined the records for 20,000 male health professionals. Researchers followed the group for 10 years and published results in 2007 in the journal Obesity. They showed that after adjusting for age and other factors, the men who ate breakfast were 13 percent less likely to have had a significant weight gain.

“Our study suggests that the consumption of breakfast may modestly lower the risk of weight gain in middle-aged and older men,” the researchers said.

The advisory committee cited this and similar research, known as “observational studies,” in support of the notion that skipping breakfast might cause weight gain. In “observational studies,” subjects are merely observed, not assigned randomly to “treatment” and “control” groups as in a traditional experiment.

Observational studies in nutrition are generally cheaper and easier to conduct. But they can suffer from weaknesses that can lead scientists astray.

One of the primary troubles in observational studies is what scientists refer to as “confounders” — basically, unaccounted factors that can lead researchers to make mistaken assumptions about causes. For example, suppose breakfast skippers have a personality trait that makes them more likely to gain weight than breakfast eaters. If that’s the case, it may look as if skipping breakfast causes weight gain even though the cause is the personality trait.

It’s a reminder of the very important rule: Correlation doesn’t equal causation. Just because one detail appears alongside another detail, it doesn’t mean the one detail causes the other. (Tall people play basketball. Therefore one might conclude that playing basketball makes people tall. Is that right?)

Similarly we’ve seen a recent revision on dietary fat and cholesterol guidelines. We once thought that fat (particularly saturated fat) and cholesterol were the most evil of edible substances. Based upon flawed science, we were told to replace fat with carbohydrates and we’d all be well. Upon further review, it seems we may have been very wrong.

Low-carb vs. low-fat

Sticking with the diet and science theme, there’s been a lot of discussion on a recent study in Cell Metabolism that looks at low-carb vs. low-fat diets. This was a six-day study in a carefully controlled lab environment. The study had the same group of 19 obese participants spend six days on either a restricted-carb or restricted-fat diet. They then went home for several weeks for a “wash-out” period where they resumed their normal eating habits. The participants then returned and they were switched to the other diet. The same number of calories were cut from both diets, the difference being the calories came specifically from either carbs or fat. The participants were observed in a metabolic chamber and their caloric expenditure was very closely monitored. It was a well-designed study.

The result? The low-fat group lost more fat. Discussion over right? If you saw most of the popular-press headlines you’d think so. But there’s more to the story.

First question in my mind is “What about protein?” Though the jury is still out on some aspects of high-protein diets, several studies (here, here, here and here among others) suggest that high-protein diets can be useful for weight loss. The study doesn’t mention protein at all. Seems odd to me in that carbs, fat and protein are the main macronutrients in food. Why would we want to manipulate and study the effects of just two?

A good discussion of the low-carbs vs. low-fat study can be found at Examine.com. Really-low-fat vs somewhat-lower-carb – a nuanced analysis goes into some of the limitations of the study. This article is quite detailed. Read it all if you’re up for it. I won’t go into all of it but here’s a little bit.

One point to remember that this low-carb diet could be called a “lower-“carb diet in that some low-carb diets go much lower than this one. The Examine.com article says:

“The carb levels ended up being 352 grams for Restricted Fat versus 140 for Restricted Carb, and the fat levels 17 versus 108. In other words, (moderately lower carb than typical diets) versus (oh my goodness I can count my fat gram intake on my fingers and toes!).

This trial wasn’t designed to explore a real-life 100-gram-and-under low carb diet and especially not a ketogenic diet. Rather, it was a mechanistic study designed so that they could reduce energy substantially and equally from fat or carbs, but without changing more than one macronutrient. If they lowered carbs much more in the Restricted Carb group (like under 100 grams), they’d then have to go into negative fat intake for the Restricted Fat group. And negative fat intake is impossible (*except for in quantum parallel universes). One more note: all participants kept dietary protein constant and exercised on a treadmill for an hour a day.”

So it’s possible that if carbs were lowered further, we might see a different outcome of the study. Also, this was a six-day study. We must wonder what might happen over the course of six weeks, six months or six years.

Another very important point to remember is that this was a very tightly controlled experiment. It didn’t reflect the real world in which people trying to lose weight have to make their own food choices. Examine.com says:

And to repeat a very important point: this study was not meant to inform long-run dietary choices. In the long-run, the choice between restricting fat or restricting carbs to achieve a caloric deficit may come down to one thing: diet adherence.

While preference for certain foods may dictate which diet is easier to adhere to, this isn’t always the case. For instance, it seems that insulin-resistant individuals have an easier time adhering to a low-carbohydrate diet. Nowadays, new dieters often pair low-carb with higher protein, the latter of which can boost weight loss. And since there are plenty of high-sugar but low-fat junk foods (see Mike and Ike, et al.) but not so many high-fat but low-carb junk foods, low carb intakes can sometimes mean an easier time staying away from junk food when compared to low fat diets.

So we should remember that the dietary rubber meets the road when someone seeking weight loss can modify their diet in any healthy way and then stick to it for the long haul. If it’s less fat then great. If it’s fewer carbs, also great. If it’s some other improvement to the diet then wonderful!

Eight glasses of water a day is arbitrary

Another sacred cow of health and longevity is the admonition to drink at least eight glasses of water a day. That bunk has been debunked but much like a bell that’s been rung, it’s hard to change people’s minds once they’ve heard this information. The New York Times gets into this topic in No,You Do Not Have to Drink 8 Glasses of Water a Day. This one is simple. If you’re thirsty then drink. If you’re not then don’t. (How else would we have made it to the year 2015 if we didn’t have some sort of very good water gauge built into our physiology? Do my cat or dog think about the measured quantity of the water they drink?)