I recently attended a course called 3D MAPS. The course was presented by Dr. David Tiberio and it was offered through Gary Gray’s Gray Institute. I enjoyed the course and learned a lot. I’m now applying the concepts I learned in both my own training and in my clients’ programs. Here’s a rundown.

Overview

What is 3D MAPS all about? The Gray Institute describes it as such:

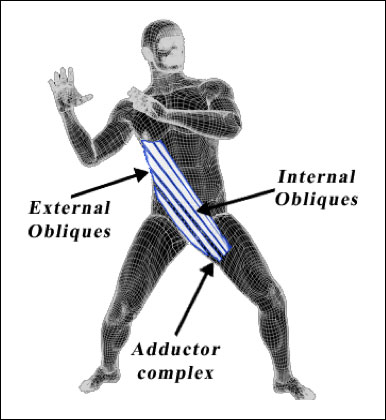

- 3D – The human body moves three-dimensionally. All proprioceptors respond, all muscles react, and all joints move three-dimensionally. It only makes sense to analyze and progress the body three-dimensionally. 3DMAPS facilitates functional assessment and much, much more!

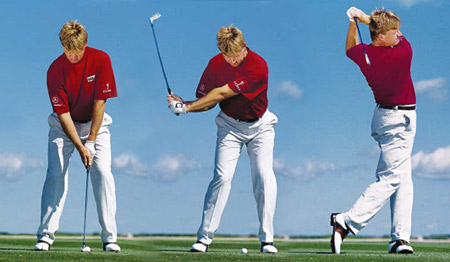

- Movement – 3DMAPS leverages movements – lunges, reaches, squats – that are paramount to common, everyday movements and activities. These movements are authentic to the individual and relevant to what the individual does. While other screens, scans, analyses, claim to be functional, 3DMAPS actually is.

- Analysis – 3DMAPS analyzes the entire body’s mobility (flexibility, range of motion) and stability (strength, control of motion) and then identifies a Relative Success Code specific to individual – based on symmetries, asymmetries, and disabling pain within the movements.

- Performance – 3DMAPS enhances the function of the individual and progresses systematically and scientifically for optimal function and improvement.

- System – Performance Movements parallel Analysis Movements, thus creating a seamless and intuitive process for both the practitioner and the patient / client.

As I see it, 3D MAPS is a movement analysis method that asks the client or patient to move through a wide range of motion in all three planes. As the client moves, the trainer continually asks “Is he/she showing adequate mobility?” and “Is he/she showing adequate stability?”

3D MAPS uses six lunges in three planes of motion to check mobility. In the saggital plane we have anterior/posterior lunges. In the frontal plane we have same-side lateral and opposite-side lateral. In the transverse plane we have same-side rotational and opposite-side rotational.

Six variations on one-legged squats are used to check stability. The same planes of motion are used as the lunges but instead of taking a full lunge step the client balances on one leg while reaching the other leg in the various different directions described above. These single-leg movements can be quite challenging and putting the foot down is allowed if needed.

In addition to the lunges and one-legged squats, clients swing their arms in the same three planes of motion as the lunges and squats.

3D MAPS movement patterns used to evaluate mobility and stability: anterior lunge, posterior lunge, opposite side lateral lunge, same side lateral lunge, opposite side rotational lunge, same side rotational lunge. The lunge images are in black. The 1-leg squats are red.

Above are the basic movement patterns used in 3D MAPS. Trainers can “tweak” (in Gary Gray speak) in our out a wide variety of movement variables to make the movements more or less challenging. For instance, clients may lunge or one-leg squat without the arm swings or they may swing the arms without the lunges and one-leg squats. Lunges and one-leg squats may move in different planes from the arm swings.

The ground reaction force of the lunge may prove too challenging for some clients. A trainer can then simply ask the client to get in the lunge position and oscillate into and out of the lunge position.

The one-leg squat variations are designed to challenge the client’s balance and stability skills. They may be too challenging especially when the arm swings are used. Therefore a trainer may allow the free foot to tap down, tweak out the arms, keep the head steady (as opposed to moving with the trunk) or allow the client to hold lightly on to something for a little more stability. The idea here is to find the limits of someone’s stability but not to totally push them over the edge of his or her ability.

As we observe the client move we take note of the right/left symmetry of the client’s mobility, stability, and whether or not there’s pain present during the process. We note their successes and deficits as part of something called the Relative Success Code. This is a way of ranking their abilities from most to least successful and it helps determine our training or treatment process.

Strengths

Based on real-life

I feel the 3D MAPS process lives up to its “functional” billing. That is, it allows us to observe movements that are specific to many real-life situations. 3D MAPS speaks to the SAID Principle which says our bodies adapt specifically to the demands imposed on us. Real-life demands us to move in three dimensions, react to gravity and that our joints, limbs and muscles all work together to accomplish various tasks. We tend to stand on one or two legs while doing these tasks. For all these reasons I feel like 3D MAPS is superior to something like the Functional Movement Screen (FMS), sit-and-reach tests, 3-minute step test, crunch test, pushup test, timed plank test, etc.

(The concept of “functional” training has stimulated my thinking. I’m writing a blog post on that concept right now.)

Feels like exercise

Most of my clients find themselves working fairly hard as we’ve gone through 3D MAPS. It feels like exercise. Not all movement analysis systems deliver this feeling to the participants. The reality is that many of our clients come to us because they want to exert and sweat. If we can gain valuable information and give our clients a workout then that’s a very good thing.

Easy to teach

The Gray Institute does a good job of teaching how to teach. Dr. Tiberio and the online videos made it easy to understand the breakdown of the movement patterns and how to progress and regress them.

Opens clients’ eyes

If 3D MAPS reveals a mobility and/or stability deficit then my clients typically perceive it. They often very clearly recognize that they’re lacking in their ability to lunge and they can always tell if they have poor balance. This is valuable in getting a client to buy into the 3D MAPS process.

Further, I’ve found that following the 3D MAPS intervention blueprint often results in noticeably better stability and/or mobility. It’s always exciting to see results!

The search for success

A very interesting aspect of the 3D MAPS methodology (and the Gray Institute process in general) is that we first want to find where and how the client can move successfully. We then want to to gradually move in on their lack of success. This is in contrast to what I think most of us want to do and that’s dive right into the task that gives us the most trouble. I think we typically want to climb the biggest, toughest obstacle before we tackle anything less significant. (Maybe that’s just me…. Nah.)

There are a couple of ideas behind the process of moving from the most successful down to the least successful movement task. One is that we want the client to feel successful and confident. If he or she can do something well and feel competent and confident then they will likely have a generally good workout experience. He or she may feel encouraged to try more difficult work.

The other idea informing the most-to-least-successful process is based on the possibility that the nervous system will best be able to solve the most difficult movement task if we very gradually expose it to increasingly difficult work. This makes sense if we think of learning anything from a language to music to driving a car to skiing. We do best if we start with very simple tasks and then progress toward more difficult territory. This process makes sense to me.

Many options

As I mentioned earlier, there are many ways to “tweak” the lunges, one-leg squats and the arm swings. Trainers can have clients move their head or not. We can ask clients to speed up, slow down, and lunge or squat farther out or closer in. We can go with lower-body or upper-body movements only and we can have clients use either the upper or lower body in ways to increase or decrease stability requirements. Beyond the assessment aspect of 3D MAPS, we can have clients hold weights, medicine balls, cables, bands, etc. if we want to create a greater challenge.

Weaknesses

Not a great upper-body assessment

3D MAPS is a very good lower-body assessment but it seems limited as an upper-body assessment. It’s very difficult to observe scapular movement quality or humeral internal/external rotation quality. Further, while we can observe mobility and stability in the lower-body, 3D MAPS gives us virtually no indication of upper-body stability.

Better for global movement assessment than local assessment

For now, 3D MAPS gives me a big picture of how the person is moving. It doesn’t reveal a lot about individual joints. My criticism here will probably lessen as I become more familiar with and more skilled at using 3D MAPS. Proper use of “tweaks” should help reveal individual joint limitations.

Relative Success Code is difficult

The Relative Success Code is supposed to be simple but it’s not and from what Dr. Tiberio said, the Gray Institute knows that there’s more work to be done. We’re supposed to score the client’s movement from their best success down to their least and then start working from their best to worst movements. But with six lunge variations and six one-leg squat variations for both sides of the body there is a lot to try and see and score. The issue as I see it is that human movement is complex and we can only simplify it so much.

Scoring should be divided into mobility and stability

This is related to the previous criticism. 3D MAPS provides tests for both mobility and stability yet we’re only supposed to give the client a “+” if they show good mobility and stability, a “-” if they show poor mobility/stability or “- P” if they have pain on any test.

If we’re testing two things it seems we should give two separate scores on each test for stability and mobility. I imagine that every trainer and therapist who uses 3D MAPS will create their own two-part score. Dr. Tiberio acknowledged this during the presentation so I’m betting the scoring system will change soon.

Many options

One of its strengths can also be a weakness. There are near infinite ways to change the testing process as well as the training/treatment process derived from 3D MAPS. Initially it’s daunting when considering all the options. Like most any new skill, the more we use it the better we get at using it. This is a minor criticism.

My overall opinion

3D MAPS gets a thumbs-up from me. I use some portion of it daily with practically all my clients. More than anything I appreciate that the driving force behind 3D MAPS is actual real-life movement requirements. I love the emphasis on three-dimensional movement. Gary Gray maybe more than anyone in the industry insists that we always look at movement through a 3D lens.

Some of this gets complicated. It does take a lot of thinking and practice to feel comfortable using the system–but what new skill doesn’t take a lot of work to master?

Dr. Tiberio said something during the 3D MAPS presentation that I found wise and valuable to me. He said, “Don’t give up what got you here.” With that he meant don’t throw out all the training methods and tools that we’ve used to become successful trainers. Don’t rush too headlong into the shiny, brand-new, hottest thing that we’ve just learned (and likely not yet mastered).

His words spoke to me and some of my past experiences as a trainer. To my regret, I’ve thrown several babies out with various tubs of fitness bathwater. There were times I was convinced that I found the absolute best, most incredible absolutely most effective tool, exercise or system and I just had to push all my clients in the direction of said new-cool-thing. While in reality two things were probably true: A) Said new-cool-thing may not have been the miracle answer to all things I thought it was, and B) Some of my previous tools, exercises and systems were still valuable. The result was that sometimes either I, my clients or both of us were frustrated. With both Dr. Tiberio’s words and my own experiences in mind, I am trying to fold 3D MAPS into my training process in a way that’s both amenable to my clients and that doesn’t frustrate me as I get familiar with 3D MAPS.

What that means is that I typically work on some of the mobility/stability issues that I see in my clients but we may not spend the whole session on 3D MAPS-related issues. We still use barbells, kettlebells, the TRX and other training tools to perform non-3D MAPS-type exercises. I have found that a very good way to work on clients’ mobility/stability issues is to put 3D MAPS exercises in between sets of say bench press, deadlift, pull-ups, etc.

Further, if someone is preparing for an athletic tasks (I train several skiers and snowboarders for instance) then their sport dictates that they exhibit athletic skill during times of fatigue. I believe an effective way of training these athletes is to fatigue them in some way (with kettlebell swings for instance) and then require them to exhibit skilled mobility/stability (with some sort of one-legged squat for instance). Thus I’ve found that 3D MAPS work can easily be used alongside whatever other training modalities a trainer and his or her clients enjoy, so hooray for everyone!

That’s about it for now. My next post will speak to the idea of functional training and exactly what that term might mean.