A couple of recent articles have me thinking…

Unfortunately for many of us, exercise and injury (or just pain) live very close to each other. I’ve heard a lot of people say things like “I can’t run anymore because of my knees,” or, “The bench press hurts my shoulders.”

Something that’s supposed to be healthy hurts us? That doesn’t sound right.

Exercise and the big picture

When “Healthy” Habits Aren’t comes from Whole 9. It’s written by Kate Galliett of Fit for Real Life. She gives discusses a big-picture view of our exercise habits within the context of our often stressful, unbalanced lives.

She says:

“Exercise is not meant to break you. Exercise habits are not meant to suck other important aspects of your health dry. Exercising is not meant to be a numbing agent to things your body is telling you.”

Seems obvious, right? Who would argue that we exercise in order to feel bad and get hurt? Yet the reality is that multitudes of gym goers, runners, and all sorts of recreational athletes inhabit a world in which their chosen activity puts them in pain every day. This picture is out of whack. Pain is a way of telling us that something needs to change. (Remember though, pain doesn’t always equal injury, but pain is not to be ignored.)

I like this:

“Chronic stress is not helpful for fat loss, muscle gain, or performance improvement. It’s also not helpful for any of the health factors that keep you alive & kicking well into your later years. And many habits society deems ‘healthy’ are much less so when looked at in context to modern, busy, stressed lives.”

And to the previous point, this is extremely important to remember:

“Stress is stress. It’s the same to your body whether you define where it comes from as ‘good’ or ‘bad.'”

Living organisms need a certain level of stress to flourish. With the right amount of stress applied in a progressive way plus rest, plus food, that organism gets stronger. Too much stress of any type plus inadequate rest and/or inadequate food and that organism breaks down. We don’t want that but that’s where a lot of us are.

Why exercise?

A lot of us identify in part by our physical activity. “I’m a runner,” I’m a cyclist,” “I’m a powerlifter,” or “I’m a Crossfitter.” Self-image matters a lot, whether or not you want to admit it. This paradigm can get a little out of control.

Sometimes it seems we get to where we’re working out just to work out. And sometimes we push harder thinking we’ll get stronger yet in reality we’ve dug ourselves a hole and we’re digging harder to get out.

“Take a break? Back off? Are you insane? That’s for losers! I HAVE TO WORK OUT! THAT’S WHAT I DO!”

Well… Okay… But are you realizing a benefit?

Not if your workout hurts you. And if you’re piling stress on top of stress on top of stress, and you’re working harder despite the fact that you’re not sleeping enough, your job is killing you and your family is driving you crazy—all during allergy season—then don’t be surprised if you feel like a wreck. It might be time to try something different.

To me, the takeaway message of the article is that the actions and habits we practice in the pursuit of health and fitness don’t exist in isolation. These practices exist alongside a wide range of other influences in our lives. There are times when we need to take a step back, look at the big picture and at times modulate our beloved running, swimming, weight training or what-have-you. Read the full article for the whole discussion.

The Wellness Continuum

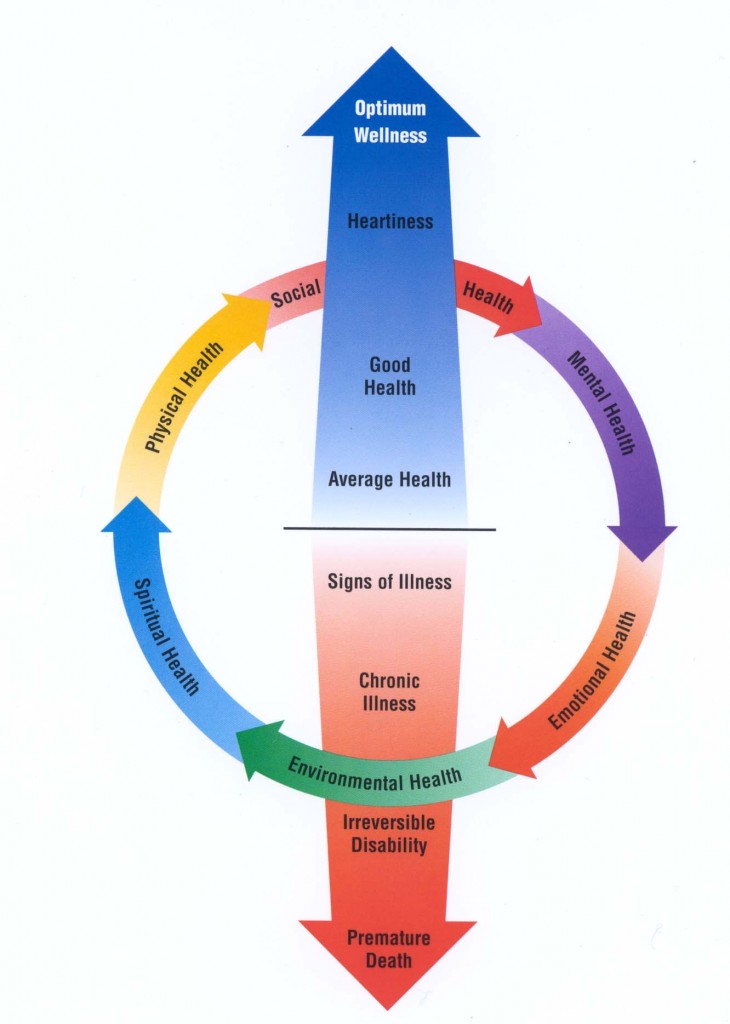

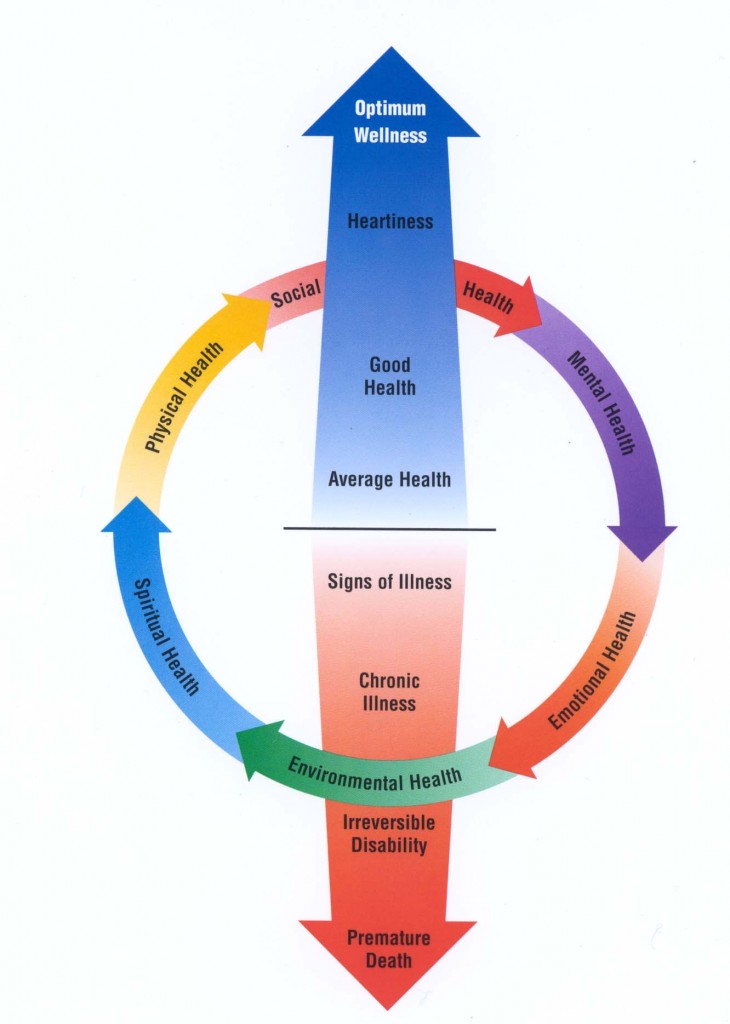

To expand a bit, this article reminded me of something I learned about in grad school, something called the Wellness Continuum.

The Wellness Continuum

I’ve talked with a lot of people who view health exclusively through the diet and exercise lens. In this view, diet and exercise are separate and distinct from all other aspects of health. To me, this view is like looking through a microscope.

With the Wellness Continuum, we can examine our lives with a telescope. We can see an amazing range of interrelated factors that contribute to or take away from our overall health. Most of us, myself included, probably do very well in some of these categories while other categories deserve extra attention.

To reiterate, none of these factors exist in isolation. These conditions all blend together to determine our well being. If we ignore one aspect of health then the whole operation is diminished.

Crossfit & Injuries

High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry comes from the Washington Post. The article discusses not only injuries that may be generated from Crossfit workouts but also the businesses that have sprung up to treat said injuries.

One observation of the article is this:

“Many people who do the high-intensity workouts aren’t adequately conditioned for such rigorous workouts, or have back and spine conditions that could worsen, said Dr. Marc Umlas, chief of orthopedic surgery at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami, who said his office has seen an increase in injuries from workouts at CrossFit and similar programs.

“’They plunge headfirst into a high intensity workout and they get injured,’ Umlas said.”

The article describes various business that offer treatment strategies for such injuries. A trainer, Lauren Roxburgh said something related to the theme of the previous article on healthy habits:

“’In our lifestyle it’s been very much about the doing. … It’s all about pushing through, doing, doing, doing, and it hasn’t been enough about the yin, which is the being, being in the moment, being present in our bodies,’ she said.”

That sounds like yoga-speak for respecting the need for rest and recovery. More more more harder harder harder exercise isn’t always better better better. There’s a time for hard work and a time for backing away from hard work.

“It depends…”

“What do you think of Crossfit?”

I’m often asked that. As with most questions, the most accurate answer is “It depends….” on a lot of things.

(To be clear, I’m not a Crossfit coach. I’ve never worked out in a Crossfit gym. I’ve met lots of Crossfitters and I’m aware of a lot of what I’ll call the Crossfit culture and its components.)

I love that Crossfit has re-popularized free-weights, the Olympic lifts and body weight training. I love that in many Crossfit facilities there is a supportive community that bonds through tough workouts. I’ve met good Crossfit coaches who recognize the need for proper technique and proper progression in doing these workouts.

I’ve also seen some horrendous exercise technique displayed by Crossfitters. I’m aware of a mentality in many (maybe not most) Crossfitters that the harder and faster the workout the better. Some in the Crossfit culture view this mentality with pride. I think it’s a questionable approach.

My answer is it depends on the condition of the individual participant. Is this a raw beginner or an experienced lifter? How well does the person move? Who’s coaching him or her? Does the culture at a particular Crossfit facility emphasize good technique and proper rest and recovery strategies? Or is it all “Go! Go! Go! Ignore the pain!”

Adaptation to imposed demands

Human beings can adapt to all sorts of stresses and conditions. As it relates to exercise; if we work in a progressive manner; gradually applying stress to our bones, muscles and connective tissue; consuming appropriate calories and nutrients; and resting appropriately then our structures will adapt to those imposed demands. (Read up on Davis’s law and Wolff’s law for more on how this process works.)

If, on the other hand, we go hell-bent-for-leather into a new workout routine (particularly if we don’t spend time on learning good exercise technique) then we may outrace our body’s ability to adapt.

To compound issues, if we undertake some sort of intense Crossfit-type workout, and our personal Wellness Continuum is out of balance then it’s highly likely that aches and pains will soon follow.

Discipline

With exercise, most people equate discipline with getting up early, working out hard every day and “pushing your limits.” I would offer that “discipline” really means doing what you need to do, not just what you want to do.

For we who love exercise, working out isn’t the problem! We love being in the gym, on the road, on the trail or in the pool. Sweating and lifting heavy things isn’t the hard part. It’s taking a break that’s near impossible! Taking easy days, letting injuries heal, doing our rehab exercises, tapering for a race, taking off-days or god-forbid, taking an off-season?! …That’s discipline.

So… There’s that.