This piece about my heel pain was in the works prior to my ACL mishap. It was great to banish my heel pain! I’m still happy about it! Now I just have to overcome this latest speed bump and all will be well.

In Part I of this post I discussed my consultations with coach Mike Terborg and therapist Nick Studholme. We were trying to figure out how to resolve some very persistent heel/Achilles tendon pain that had been with me for several years. Their work was biomechanical in nature. They helped me to move better, run better and unload the sensitive tissues.

Here in Part II I want to discuss another important component to pain management, one that has less to do with biomechanics and everything to do with how we think about pain. Z-Health is where I first learned about these concepts. I drifted away from Z-Health a bit but I’ve returned to my learning about the realities of pain.

Key points

- Pain is in the brain.

- It’s a blend of nociceptive (danger) signals, attitudes, beliefs, past experiences, knowledge, social context, sensory cues.

- It doesn’t equal tissue damage–particularly in chronic pain cases like mine.

- Pain is a response to a perceived threat.

- Reduce the threat and we reduce the pain.

Obviously there’s a lot of subconscious stuff at work when we experience pain. If we want to tie our shoes or turn the ignition key of a car, we have to consciously take action to make these things happen. In contrast, we don’t have to think at all in order to feel pain. We feel pain without having to consciously do anything. However, research into pain reveals that we can often actually reduce our pain via cognitive processes.

One of the most powerfully fascinating aspects of pain management involves consciously considering pain and whether or not we’re actually under threat. Emerging research strongly indicates that pain management can be made more successful by educating a patient about the whole pain process. Understanding the process at work and recognizing that pain DOES NOT equal injury and that it IS NOT a threat to our health or life can be hugely powerful. For instance, there’s this analysis of research titled. Patient education interventions in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analytic comparison with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug treatment. The conclusion is this:

Based on this meta-analysis, patient education interventions provide additional benefits that are 20–30% as great as the effects of NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) treatment for pain relief in OA and RA, 40% as great as NSAID treatment for improvement in functional ability in RA, and 60–80% as great as NSAID treatment in reduction in tender joint counts in RA.

Here, patient education offers benefits beyond that seen with drug treatment alone.

Exercise Biology explains pain:

Exercise Biology is a fantastic, very thoughtful site full of very useful information. It’s written by Anoop Balachandran. He’s gone to admirable lengths to include only evidence-based information and science. It’s not just opinion. One of the best articles on his site deals with pain science. It’s called What should fitness professionals understand about pain and injury? and it does a great job of breaking down a complex subject digestible pieces. (Todd Hargrove at Better Movement also does a great job discussing pain in a similar way.)

Very pertinent to my experience is Anoop’s discussion of how to desensitize or calm down a nervous system that is overly sensitive to a perceived threat that no longer exists. He describes the top-down vs. the bottom-up (find-it-and-fix-it) approach:

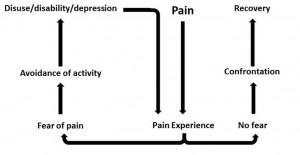

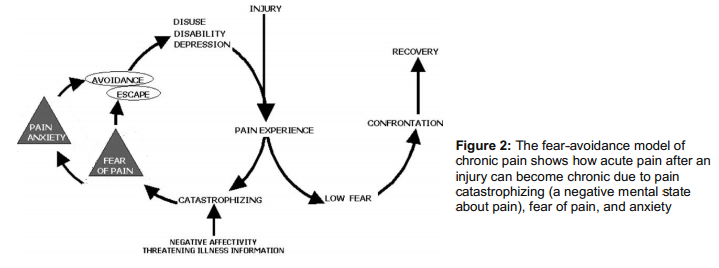

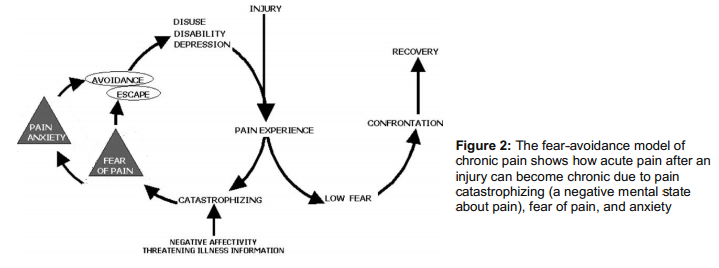

Top Down: Basically, means changing your attitude, beliefs, knowledge (neurophysiology of pain) about your pain and in turn, lowering the threat value of pain. People get hurt, they experience pain, healing follows, and they recover. But in some folks the pain lasts forever. And why is that? According to one of the most well-accepted models – the fear-avoidance belief model – people who have heightened fear of re-injury and pain are good candidates for chronic pain. Lack of knowledge or incorrect knowledge, beliefs ( hurt always means harm, my pain will increase with any activity and so forth), provocative diagnostic language and terminologies used by medical therapists like herniated disc, trigger points, muscle imbalance, and failed treatments can further heighten this fear or threat . So education to lower the threat is THE therapy here. We now have some very good evidence to show that just pain physiology education or the top-down approach is enough to lower pain and improve function 5.

Bottom Up approach: The bottom-up approach is what we see around us: surgery, postural fixing, trigger point, muscle imbalance, movement re-education, manual therapy, acupuncture and the list keeps growing. Almost all treatments out there are trying to lower the nociceptive drive without much consideration to the top-down approach. This is solely because these treatments are based on the outdated model of pain. We now suspect that positive effects of manual therapy may be due to neural mechanisms than the tissue and joint pathology explanations that is often offered. So even the bottom up approach is working via de-sensitizing the nervous system. Although not intended, there are top-down mechanisms clearly at work even in bottom up approaches( like the placebo effect, a credible explanatory model, the belief in the therapist) .

So what we you need is a combined approach that takes into account the “entire individual” and that’s where the biopysycosocial model of pain treatments walks in. The bio psycho addresses the biology (nerves, muscle, joints), psychological ( beliefs, thoughts, fear) and social aspects (work, culture, & knowledge).

Pain self-talk: “I’m not in danger.”

My Achilles started feeling a lot better once my running biomechanics were cleaned up (the bottom-up strategy.) I still had some sporadic discomfort though. In reading up on pain and the brain, I realized it was time to apply the top-down method. I had several internal conversations with myself. I said something like this: “I’m not under threat. My Achilles is strong. It won’t break. I’m safe and strong and I’m ready for anything that comes my way.”

I started feeling a little like Stuart Smiley as I gave myself these pep talks–but guess what!–they worked. Literally within 48 hours my residual pain was gone! This conscious thinking process seemed to influence the unconscious pain process to a very favorable result.

The pain neuromatrix

This model is known as the pain neuromatrix. and it is very powerful stuff. It may sound odd this idea that pain and injury aren’t the same, and that pain can be changed literaly through education. I haven’t made any of this up though. This is what the researchers are finding.

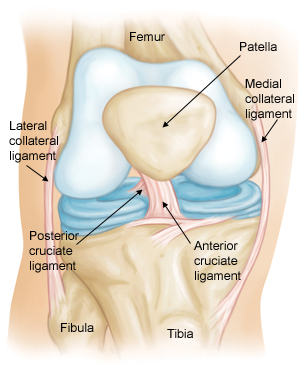

My ACL injury and pain

I sustained an acute knee injury that includes a torn ACL. Did it hurt? Oh yes! It was a sudden change that my brain rapidly assessed as a significant threat. The result of the injury is instability in my knee and I can’t move as much or as well as I could prior to the injury. From an evolutionary standpoint, I’m at a disadvantage for survival. Pain is helping me avoid further damage. I will most likely undergo an ACL reconstruction (I hope to know for sure next week.) with plenty more pain to go along with it. But I’m not worried.

I went through 10 years of weird chronic pain (primarily low-back pain) that didn’t have an obvious cause. I obsessed over it and dreaded the pain constantly. I missed out on perhaps my best potential years as an athlete. I overcame it though. (Much of my relief came from the bottom-up approach of fixing a lot of biomechanical issues–which ultimately reduced the threat level to my brain.)

Now with that perspective and my current knowledge, here’s how I see my knee injury:

- I’m highly optimistic that I can be fixed and that I can return to all the activities I love.

- I’m exercising as much as possible while at the same time avoiding pain. In this way I’m calming my brain and minimizing any feelings of depression, 2nd guessing, or any “woe-is-me” thinking.

- The threat level via my knee will be high. Therefore:

- I must be patient and diligent with my rehab. I will!

- To reduce threat, my return to exercise (particularly Olympic lifting, trail running and skiing) must be gradual and non-threatening.

More resources:

Lorimer Mosely is one of the foremost pain experts on earth. Here he lectures on pain. Around the 7 minute mark he discusses his own experience with a very dangerous yet painless wound. The whole thing is fascinating but perhaps a bit long for some. If you’re in pain though I strongly suggest you watch it.

Also, here’s a link to an interview by Bret Contreras with physical therapist Jason Silvernail. Many good questions are asked and very well-informed answers given. Again, it might be long for some of you but the information is just hugely valuable.

Remember, learning about pain can help you overcome pain! Reading and listening to those who understand pain can be hugely beneficial to anyone who suffers. Below are more resources.

Informative sites:

www.somasimple.com (excellent forum)

www.bodyinmind.org

www.forwardthinkingpt.com

www.bboyscience.com

www.saveyourself.ca

www.bettermovement.org

www.thebodymechanic.ca

Excellent books:

Beginner Level

- Explain Pain by David Butler & Lorimer Moseley (This is a must read)

- Painful Yarns by Lorimer Moseley

Intermediate Level

- Pain by Patrick Wall

- The Challenge of Pain by Ronald Melzack

- Sensitive Nervous System by David Butler

- The Back Pain Revolution by Gordon Waddell

- Topical Issues in Pain by Louis Gifford

- Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching patents about pain by Adriaan Louw ( a book on how to do the top down approach)

- Pain by Lorimer Moseley (DVD)