… this is basically Newton’s First Law applied to habit formation: Objects in motion tend to stay in motion. Once a task has begun, it is easier to continue moving it forward.

– James Clear

An important task stares us in the face. We vegetate and pray for supernatural intervention to either complete the task or remove it from existence. We know the task is important to our health and wellbeing. But our emotions undermine us and we avoid the gym, delay meeting with a financial planner, or avoid scheduling an appointment with a doctor or mental health counselor. Or we just hope the lawn will mow itself.

The search for motivation is common to everyone. I’ve spent weeks at a time not posing on this blog but knowing that if I want to be a writer then I must write. The dread and self-loathing builds… I may long to improve my physique and drop some body fat, yet I eat the same: I love a cocktail and some dessert—and those flabby trouble spots refuse to budge! Grrrrr! The inconvenience of it all!

We believe that Motivation, a gleaming white stallion, will gallop in from nowhere and carry us effortlessly to meaningful action—but that doesn’t happen. So there we sit, pining for that magic horse. We got it wrong. Action breeds motivation.

If we take a small step and find just a little bit of success, then we tend to want to see more success so we take further action. Several writers have discussed the action-creates-motivation dynamic.

Brad Stulberg writing in Outside Online discuses the dip in motivation during the pursuit of a goal:

“But then, when the first rough patch inevitably hits, motivation dwindles. This is when you decide to sleep in on winter mornings instead of go for a run (failed exercise plan), eat carrot cake at 11 p.m. (failed diet), or ignore your romantic partner when they tell you about their day (failed relationship goals). Even though you still want to accomplish your objectives, you may stop caring as much about them. And yet if you force yourself to show up, to take action—do the run, skip the cake, be present for your partner—and if you do this consistently, a strange thing starts to happen: Your motivation increases.”

Dr. Rubin Khoddam writes in Psychology Today explains how taking committed or valued action leads to more motivation to take more action:

“Let me give you a basic example. Have you ever felt like just staying at home and watching TV and not motivated at all to go to the gym? Yeah, me too. BUT, have you also ever noticed that you sometimes went to the gym and not only felt better about yourself but were more motivated to go back again later. That is because motivation does not precede action, action precedes motivation.

“I don’t just mean any action. I mean committed action. Valued action. What is valued action? Valued actions are actions that are consistent with your values in life. These are actions that are consistent with the type of person you want to be. I value staying healthy, so I set a goal for myself to go to exercise at least 4 days a week. My valued action is getting my butt up and going to the gym regardless of whether I am in the mood or not.”

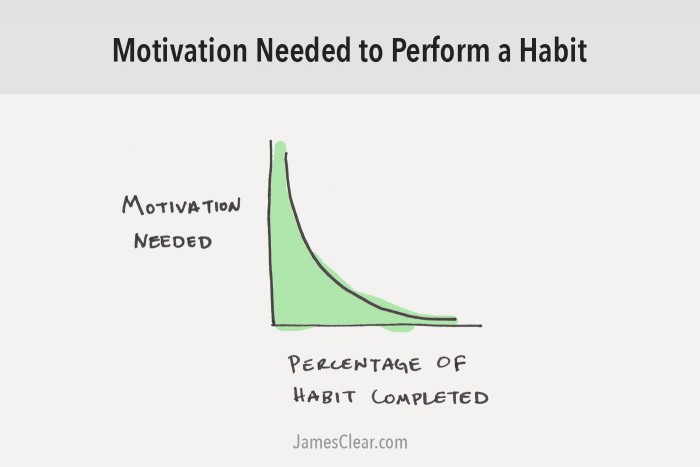

James Clear has written an extensive article on motivation. He discusses common misconceptions about motivation:

“Motivation is often the result of action, not the cause of it. Getting started, even in very small ways, is a form of active inspiration that naturally produces momentum.

“You don’t need much motivation once you’ve started a behavior. Nearly all of the friction in a task is at the beginning. After you start, progress occurs more naturally. In other words, it is often easier to finish a task than it was to start it in the first place.

“Thus, one of the keys to getting motivated is to make it easy to start.

Clear also discusses the power of the Goldilocks Rule to stay motivated over the long haul:

“Human beings love challenges, but only if they are within the optimal zone of difficulty. Tasks that are significantly below your current abilities are boring. Tasks that are significantly beyond your current abilities are discouraging. But tasks that are right on the border of success and failure are incredibly motivating to our human brains. We want nothing more than to master a skill just beyond our current horizon.

“We can call this phenomenon The Goldilocks Rule. The Goldilocks Rule states that humans experience peak motivation when working on tasks that are right on the edge of their current abilities. Not too hard. Not too easy. Just right.”

Each of these articles mentions physcial movement as a part of motivation. Sitting still saps our motivation. Movement generates motivation. Get up. Move around. Do something that moves you forward, even if it’s just one step. The motivation will follow your action.

while running:

while running: