Everyone and anyone who’s been in a gym has heard the phrase “No pain, no gain.” What does that phrase really mean? Do we want our clients exercising in pain? What should effective exercise feel like?

In my experience, clients often interpret “No pain, no gain,” as “Pain is inevitable and it should be ignored.” I believe that for the good of our clients’ health, trainers should examine this misunderstood statement with their clients. This is a vital conversation, especially with clients who are new to training.

Pain & discomfort defined

I don’t recall if it was in a seminar or an article, but someone smarter than I once discussed pain vs discomfort. I’ve stolen the idea and used it ever since. (If you made this description and you’re reading this then thank you! It’s been highly valuable to me and my clients.)

My clients should understand that in order for exercise to do the things we want it to do — if we want to create favorable adaptations to exercise — then a client must exercise to the point of exertion and fatigue. The client must work hard. He or she might sweat, grunt, groan, and work to the point of fatigue and discomfort. A description of the D-word:

Discomfort:

- Often a burning in a working muscle or muscles.

- Comes with a feeling of fatigue.

- Doesn’t alter the way you move (compared to a limp, for instance)

- Is usually symmetrical if for instance you’re squatting, swinging a kettlebell, doing pushups, running or cycling.

Discomfort is a sign that we’re working near your accustomed limits. That’s a good thing, and that’s how you get in better shape.

I also tell my clients about pain. We don’t want pain. (Some minor, intermittent pain may be OK. More on that in a moment.) Some characteristics of the P-word

Pain:

- Often felt in a joint, not a muscle

- Sharp or electric

- May not accompany fatigue

- Severe pain alters your movement: Knee pain causing a limp or low-back pain altering how you bend down and pick up something

- It’s often asymmetrical: Knee pain in one knee when squatting, shoulder pain in one shoulder during pushups or bench press, low-back pain on one side of the low back

If a client feels pain then we stop and we evaluate. Persistent, serious pain should not be a part of our day-in-day-out experience at the gym. Pain is not something to be ignored or masked with pain pills. Pain is a signal from the brain that something isn’t operating as well as it should be.

Color-coded pain

In another case of I-forgot-where-I-read-it disease, I read about a physical therapist’s color-coded, traffic-light guide to pain. I’ve adopted it and it helps guide me as to when to when or if I need to alter an exercise for a client due to pain. It goes like this:

GREEN: Everything feels fine; no discomfort anywhere. Client is ready to rock ‘n’ roll!

YELLOW: Minor, sporadic, or short-lived pain during the exercise but it’s not bad enough to stop or alter the movement pattern. We keep going as long as it doesn’t get worse.

RED: It hurts. We stop.

If pain becomes more intense, and/or more frequent, and/or lasts for more than a week then it’s probably time to seek medical care of some sort. Trainers should have a physical therapist, chiropractor, or some other licensed medical professional to whom he or she can refer clients.

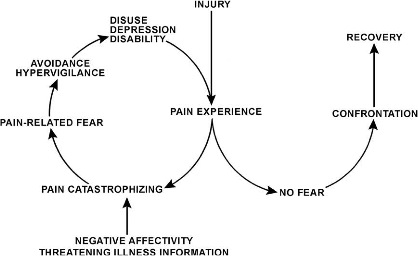

I like this code system in that it’s rare that everyone is going to feel 100% perfect all the time. It’s not uncommon for us to feel something that is less than optimal but not so bad that we need to stop entirely. With the yellow reading, we can keep going through some minor pain, and we can avoid catastrophising around pain. If a client can experience a little bit of pain yet continue working then I think we can build resiliency in the client and protect against what’s known as fear-avoidance of certain movements. If we get to red then we can always stop and change things.

Unfamiliarity: Is it pain or discomfort?

Exercise newcomers may have no idea what it feels like to work hard. Their experience with muscular discomfort may be sporadic and in the distant past. Unfortunately, many people experience all uncomfortable feelings the same whether it’s joint pain or the normal sensation of hard work. They are different and our clients should learn the difference.

A classic example is low-back pain/discomfort. The epidemic of low-back pain is a unique pain in our culture. It is widespread and debilitating for many thousands of people. For those who suffer low-back pain there can be tremendous fear of recurrence. At the same time, exercise is an effective antidote for many forms of pain in older people, and for chronic (but not acute) back pain.

Numerous muscles attach in and around the low back. The glutes, erector spinae, lats, obliques, and other spinal muscles live and work all around the low-back area. Just like any other muscle, if you work these muscles hard then you’ll feel it. Exercises such as squats, deadlifts, kettlebell swings, and bent over rowing can cause serious — and totally normal — discomfort in the low back. Yet for many clients, any sense of low-back discomfort can be bad and scary. Thus it’s very helpful and reassuring to a client if a trainer can discuss the issue of pain vs. discomfort.

The spirit of “No pain, no gain”

The knowledge behind that phrase is well-informed and comes with good intentions. Plus, it rhymes! It sounds good. But clearly it can be misunderstood. (If I ruled the world, I’d change the phrase to “No discomfort, no pain.”) The truth is, no one will increase his or her physical capacity by sitting comfortably. Anyone who wants to get in better shape must work hard. At the same time, pain, as I described above, isn’t a normal part of working out. Pay attention to it. Get help if it doesn’t go away.