All human movement occurs in three planes. Forward/back movement occurs in the saggital plane. Rotational movement happens in the transverse plane. Side-to-side movement take place in the frontal plane. This post is about the very easily overlooked frontal plane movement known as hip adduction.

His left hip is adducting.

(Adduction’s opposite twin is known as “abduction,” or movement of the limb away from the body’s midline. I have no idea why it was named abduction. I think it should’ve been named “out-duction.”)

Hip adduction. What is it?

Look at his right hip and you’ll see adduction. HIs leg has moved toward his body’s midline.

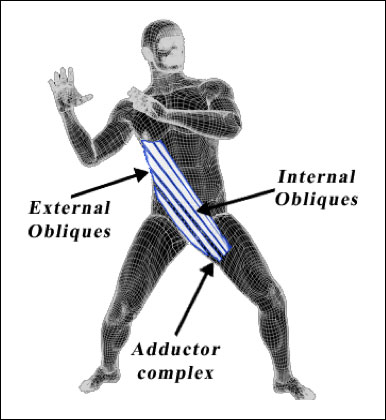

Adduction is the movement of a limb toward the midline of the body. If we think of the hip then we’re looking at the pelvis and the femur moving toward each other. Hip adduction can happen either with one leg off the ground and the leg moving toward the pelvis (Think of a soccer kick.) or it can happen with the foot on the ground and the pelvis moving toward the leg. (This should happen every time we take a step.)

Hip adduction is vital for everything from walking and running to skiing. Two aspects of hip adduction must be considered. First we must be mobile enough to achieve hip adduction. Equally if not more important, we must be able to control movement into and out of hip adduction.

Why is hip adduction important?

-

Without it, you have problems.

All of our limbs and joints are connected. We are a closely linked system of systems, not just a bunch of individual parts. What happens in one part of the body can strongly influence what happens elsewhere in the body.

The image on the right shows excessive hip adduction during gait. Too much of this may lead to knee or back pain. It’s also indicative of poor balance skills.

With that in mind, consequences of poor mobility and control of hip adduction can include back pain, hip pain, knee pain, ankle/foot problems and even shoulder or neck problems. Issues such as IT band syndrome and hip bursitis may be consequences of poor hip adduction skills.

Clients with balance problems often have poor hip adduction abilities. Their hip abductor muscles on the outside of the hip are often tight which limits their ability to move into adduction. This shows poor mobility. Typically, when they try to stand on one foot, the unsupported side drops uncontrolled into adduction which shows poor adduction control.

(Sometimes I hear clients say, “I think it’s just a balance thing,” as if balance were some ephemeral, magical thing that has no relation to muscles, limbs, joints and control of those parts via the nervous system. Balance isn’t “just a thing.” It’s a movement skill that is learnable and unlearnable.)

Preparing for a backhand, his left hip undergoes hip adduction.

Sports performance may suffer due to hip adduction problems. Significant hip adduction skills are required for effective skiing, running, golf, and tennis to name a few sports. Without good hip adduction skills, an athlete may not be as fast, powerful and effective as he or she may wish.

During the backswing, his right hip undergoes hip adduction. Follow through has hip adduction occurring in his left hip. If a golfer can’t adduct on both ends of the swing then there will likely be problems with the shot.

In Part II of this post I’ll show not only how to mobilize the hip into adduction but also how to build strength and stability.