The word “awesome” is thrown around in a casual way. You go to a restaurant and order the onion rings and the server may exclaim, “Awesome!” with genuine earnestness and enthusiasm. Now, I love onion rings but this type of thing does not actually generate anything a reasonable and honest person would call awe.

Puny humans! (click for the original pic)

In contrast, my experience at the Moab Trail Marathon absolutely filled me with awe. Both the environment and the effort were like nothing else I’ve experienced. The language fails me and I can’t adequately describe my enthusiasm and wonder about the whole event.

Moab is another planet.

The Scorched Earth Wall. A fiendish foe. (Photo: Allison Pattillo | Competitor.com)

I’ve seen pictures and they fail miserably to portray the truth of the land. I come back to the word awesome… and that word fails too. The size and scale of the rocks, cliffs, canyons, vistas and mountains was titanic. It bordered on terrifying. (This is coming from someone who lives near and ventures frequently into the Rocky Mountains.)

It is a no-joke hostile and potentially dangerous place too. We ran over, jumped down and over and slid down some very unforgiving terrain. A wrong step could have caused major problems and all sorts of injuries. (I’m not saying this to tell you how daring I am but I need to describe the terrain accurately.)

The ground was very dry for the most part but there were some muddy spots and we had to run through a few streams. The vast majority of the terrain was the classic Moab concrete-like slick rock but I was surprised at the amount of sand on the trail. I hadn’t expected that. Nor did I expect to begin the day the way it began…

The Universe has a sense of humor.

Athletes in all sports often have game/race-day rituals and we don’t like to stray from those patterns much at all. It’s rarely a good idea to experiment with things like pre-race breakfast or any part of race-day nutrition on race day. I brought my typical multi-grain hot cereal, nuts, fruit, butter and protein powder that I planned on cooking in the breakfast room. I would have that with two cups of coffee then about 1/2 hr before the race I would down three scoops of UCAN with coconut milk. Too bad the electricity went out in Moab at 4:30 AM.

So I was up extra early. (My wave started at about 8:20 AM.) There was nothing hot to eat or drink at all. I couldn’t go hungry so I downed all the cereal makings except the cereal itself. (Wasn’t sure what uncooked multi-grain cereal would do to the GI tract.) I couldn’t buy an energy drink or coffee in any stores because they were darkened and the cash registers didn’t work.

Looking down from Scorched Earth. The La Sal mountains are way back there with the snow. This pic doesn’t come close to portraying the drama of the place. (Photo: Allison Pattillo | Competitor.com, click for the original pic.)

No caffeine?! What sort of sick joke was the universe playing on us?! (Perhaps my long-departed, sadistically funny Uncle Roy had been put in charge of events on earth…)

This story doesn’t get a lot more interesting. Panic and anger wasn’t going to help. This episode was a minor hiccup. I was fed and adequately caffeinated by race time and I felt rested. A lesson has been learned: Bring an alternative breakfast and an energy drink next time.

Notable and notorious highlights

Two sections of the race stood out. Well, let’s be clear. Every inch of the whole race was dramatic in an operatic kind of way. It was all soaring and full of perfect, humbling, breathtaking solitude. (Do you get what I’m saying? There was a lot of cool stuff to look at.) My thoughts return to two sections: one beautiful and amazing, the other, nasty and maddening.

The climb up the Scorched Earth Wall was the sort of thing to challenge Godzilla. If you’re a Game of Thrones fan, this bit of geography looked like the Wall if the Wall were built on a desert on Mars. This was about 1000 feet of climbing in about 1.5 miles; all of it on hostile, dry, red, broken rocks. It it started around mile 14.

This leviathan towered to my right, looming like red storm clouds. At first glance it almost brought hysterical laughter. The psychological effects were semi-devistating. I’d encountered this type of thing on long bike rides in the mountains. The idea of running/walking up this incline was a cosmic joke that would cause Sisyphus to weep! The height and distance were massively intimidating. Looking up this eminence I could see tiny moving specks which turned out to be my fellow competitors moving up and up and up. I had work to do.

I walked most of this thing but I ran what sections I could. Mentally I wanted to slow down and plod. I didn’t though. I marched as fast as I could and I passed maybe 5-10 people.

The views from Scorched Earth Wall were splendidly desolate. This was the only place where I regretted not bringing a camera. Looking back from the trail I could see the La Sal Mountains which were powerfully enchanting as their snow-capped peaks contrasted with the red, desert-like rocks of my immediate surroundings. All of this dramatic massive scenery was tremendously humbling to my minuscule human existence.

Another part of the race was far less inspiring and wonderful. It was more of a cruel and brutal joke. Whatever malevolent supernatural force had cut the power this morning had also clearly influenced the race course design.

At just past mile 21 I could see the finish. It was a ways away but I could see and hear the end of the race! I had to run a stretch of trail along the Green River and I would be right in the neighborhood of the finish. Almost done! But “almost done” in a marathon can be an eternity of anguish.

Once to the finish area I still had three miles to go in sort of an out-and-back lollipop loop. This was no victory lap. It was horrendously difficult. I still had a rope ascent and descent as well as tough running up and down very challenging terrain.

(Let me be clear: My mom may read this blog post so I won’t use my foulest language to express my experience over this final stretch. I invite you to insert all the foul words you’d like though. I recommend a liberal sprinkling of the S-word, the F-word, a couple of words that start with C, a multi-syllable word starting with M. You may know others. Use them!)

Muscle cramps had been threatening for several miles. I felt like I could cramp to death at any moment. I truly thought at any moment I would experience a body-wide muscle seizure from my eyelids to my toenails and I’d be reduced to crawling. I was particularly fearful of cramps while doing the ropes section.

This wasn’t true mountain climbing up some vertical surface but it was using a rope to climb up and down very steep inclines. At this point in the race, this was nothing to take lightly. A cramp and/or a wrong move would likely result in some serious and ugly discomfort at best.

By some amazing miracle, I never was leveled by cramps and I have no idea why. I did manage to lose the trail right near the end so I was rewarded with about an extra 200 m of running, again proving that the universe is a perverse practical joker.

My training worked.

Winner Mario Mendoza navigates the rope ascent.

The modified Hansons Marathon Method plan worked very well for me. I felt strong and able for the vast majority of the race. The plan had me running lots of miles and many of those miles were run on tired legs. As difficult and tiring as the training was, it was exactly the preparation I needed.

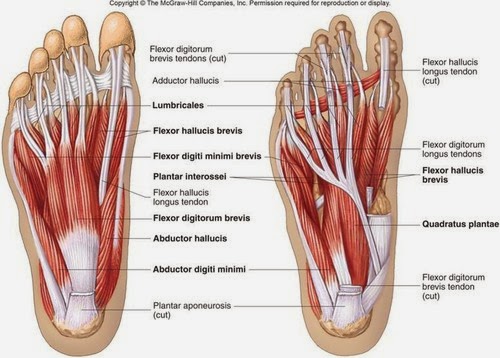

I also believe the weight training I did was very effective in preparing me for the run. There was significant climbing in which I had to step up over and over and over…. and over. That meant my glutes, hamstrings and adductors did a lot of work.

I did step-back lunges with a barbell on my back for several weeks prior to the race. This exercise did a nice job of preparing those muscles and that movement pattern for the work to come.

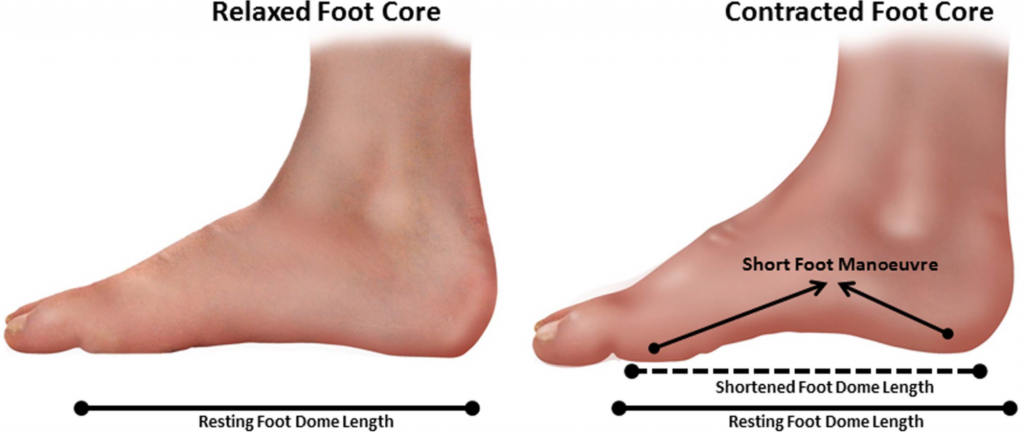

Finally, a significant point of pride for me is that I overcame several injuries and aches and pains prior to this race. My ACL was rock solid and I had no knee pain. My perpetual Achilles/heel issue were no where to be found. I vanquished these foul foes to past it seems.

I will give much thanks to Denver-area chiropractor Nick Studholme and Boulder-area movement coach Mike Terborg. They were absolutely critical to my completing the race. It’s also nice to have a wife that encouraged/tolerated all my training.

Next time

I have some very definite ideas on how to better train for this race next time. As I just said, the step-up/lunge movement pattern is essential for this race. I had to move this way while in a significantly fatigued state. Unfortunately, near the end of the race I felt serious cramping sneaking in, particularly in those stretched-out, stepping-up type of situations.

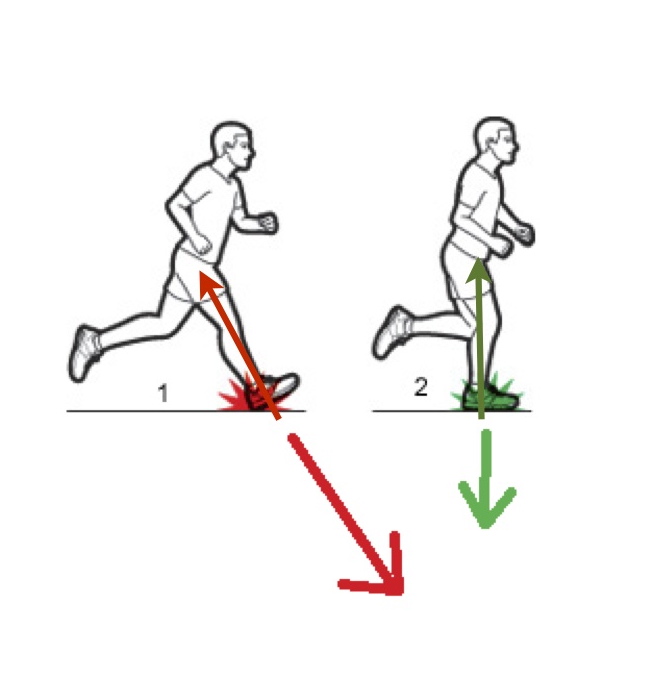

(Contrary to popular belief, cramping doesn’t seem to be very closely related to either hydration or electrolyte status. Rather, as discussed here and here, cramps are more likely brought on by a very high effort and the associated intense and repeated muscle contractions of that effort.)

The SAID Principle dictates that I train along the lines of both the specific movement requirement (stepping up repeatedly at varying angles while in a fatigued state) and energy system requirement (highly exerted and fatigued.) My idea is to complete a long run and then do a high volume of step-ups (either at the gym on a plyo box or a picnic table near the trail), weighted step-back lunges, and various 3D lunges both up on to and down from various boxes. I’ll also do some jumping down in this fatigued state as the run frequently required me to jump down from rocks of various heights and land in control.

Ya got a beer?

Finito

The post wouldn’t be complete without a little blatant display of my abilities. Full results are here.

- Net time: 5:20:31 (I was hoping for an under-5-hour finish but I’m pretty pleased with this.)

- Overall place: 171 out of 486

- Place by gender: 141 out of 303

- Place by age category (40-44): 17/41

I found my wife and a couple of friends right at the finish line. I plopped down and very quickly my thoughts coalesced into along the lines of, “I don’t want to train for another marathon for a while. Maybe never.” I was cooked. Spent. Demolished. Wiped out. Eviscerated. I was real damn tired too. I was looking forward to some serious eating and drinking, a soak in the hot tub and NOT running for a little while.

This was a grueling experience. The race was just the capstone of the process too. Training for this thing took a lot of time and involved frequent strenuous effort. Weekends were dedicated to long runs and resting. I spent a lot of weekdays in a semi-stupor. By the finish I was fairly certain that it would be a while until I ran another such race. Not for nothing, I’m also one of those runners who develops blisters under his toenails. Several. You do the math.

Fast forward to Tuesday, 72 hours after the race. As I reflect on this event I keep saying to myself, “I don’t know how I CAN’T run this again.”