My wife, our friend, and I recently completed a big hike, known as the Four-Pass Loop in Colorado’s Maroon Bells Wilderness. That part of Colorado is a truly world-class mountain wilderness. Mention “Colorado,” and most people will conjure images of this place in their minds. The scenery is as dramatically breathtaking as as anywhere on this planet. We were surrounded by massive 14,000 ft. peaks, high alpine forest, natural mountain lakes, and waterfalls. It’s difficult to describe how spectacular this trip was. I highly recommend it to anyone with a taste for outdoor adventure. Just be prepared. This trek was not a casual, easy jaunt.

The hike covered about 28 miles (Mileage varies depending on where you enter the loop.) and crossed four high-mountains passes each one above 12,000 feet. We took 2 nights and about 2.5 days of travel to get the job done.

We carried about 30 lbs. of gear and food on our backs. The pack weight plus the elevation and the frequently very technical rocky, rooty terrain made this trip especially challenging. I’m happy to say that while it was by no means an easy task, I felt good, strong and entirely up to the event. I was pleased with my conditioning for the trip. Here are some notes our my preparation.

Specific hike training: Hike!

As I’ve said before in this blog, the best way to prepare for a specific event is to do the event. In this case, we planned to hike anywhere from 6-10 miles per day, over high mountain terrain, with heavy packs. Thus our training consisted of several long hikes with loaded packs. In addition to weekend hikes, we spent several weeks wearing our packs during daily walks with our dog. The idea being that we needed all the time we could get wearing loaded packs. We might’ve looked odd walking the streets in big backpacks, but oh well. Let that be someone else’s concern.

To be clear and emphatic: The best training for hiking, is hiking.

I’ve been running and cycling for most of the year. I believe both activities have helped provide me with the type of cardiovascular ability to sustain multi-hour hiking at high altitude.

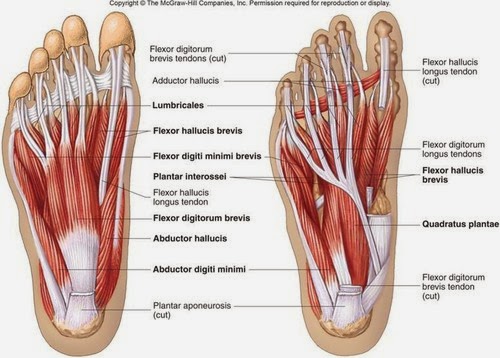

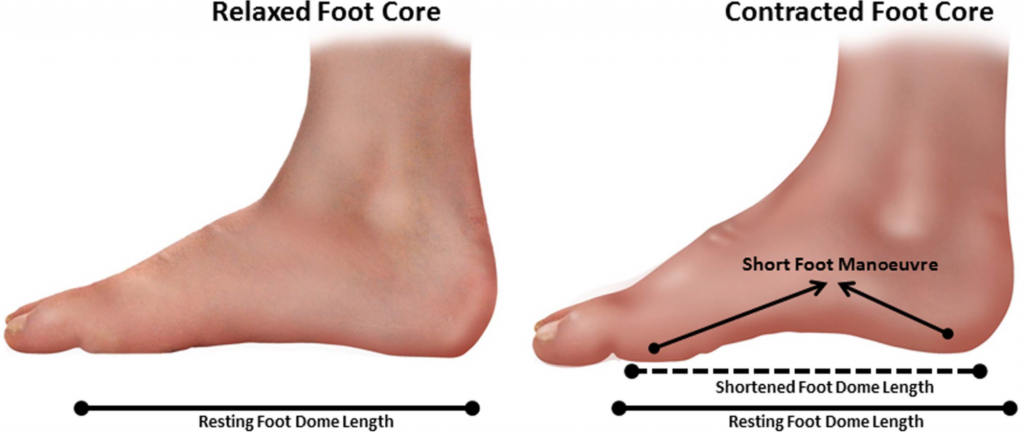

Going back to the idea of specificity, trail running is a close relative of hiking and is a clear choice of exercise for hike preparation. Trail running seems especially effective at preparing not only my heart and lungs but also my feet and ankles for the demands of extending hiking. Walking and running over uneven ground requires the feet and ankles to move through a galaxy of angles and it’s a great way to fortify those lowly and under-appreciated appendages.

The muscles of hiking and weight training

Marching uphill is especially demanding of hip extension and the requisite muscles, particularly the glutes and hamstrings. In contrast, hiking downhill requires strength and endurance of the quads and control of the pelvis by way of the hip abductors. Lost balance and a nasty fall may be the price for poor pelvic control.

With these ideas in mind, I’ve spent much of the spring and summer doing exercises such as lunges, split-squats and step-ups. Those exercises seem very effective for addressing the demands of hiking.

I particularly like what I call offset lunges, split-squats and step-ups. These are done by holding a kettlebell or dumbbell on one side of the body, thus creating an asymetrical, offsetting effect which presents different demands than a typical squat or deadlift.

If we look at real life—particularly hiking—it’s rare that we’re balanced evenly on two legs while working against a load that’s distributed in a symmetrical way on us or against us. So I believe that exercises in which one leg is doing more/different work than the other while the forces of gravity are applied in asymmetric ways are very valuable. (Not that more conventional, symmetrical exercises aren’t of value.) Here are some of those exercises:

I also started deadlifting several weeks prior to the hike. Even with a properly fitted pack, there is a lot of weight and work going through the back and hips. I knew I’d be putting on and taking off a heavy pack and I thought a deadlift would help prepare for that task.

Upon review, I believe a back squat or a good-morning might be superior to the deadlift in that each of those exercises put weight on the back, thus resembling a loaded pack on the back. (See, symmetrical exercises are good too!)

The future

I’m contemplating running the 4 Pass Loop. Others do it (Read some accounts here, here, here, among others.) and though it’ll be a fairly massive bite to take, I think it’s in the realm of possibility for me. I was very happy with the speed with which I was able to move during the hike. I’m thinking of what it would be like with a lot less gear, lighter shoes, etc. I think it’s feasible. So I ordered my first running vest and I’m contemplating what I’ll need to pack into it. The big run might happen next year…