Thanks to Denver-area trainer Jamie Atlas of Bonza Bodies and Boulder-area trainer Mike Terborg of MPower Movement for contacting me regarding my last post and giving me the name of Neil Poulton (also here). He is Physioblogger and he’s located in the UK.

Injury Rehabilitation

Check Out Physioblogger.com

StandardPhysioblogger.com is a fantastic blog with all sorts of detailed and concise information on movement, injury rehab and all such things. I actually cannot figure out the name of the person who puts it together but whoever he or she is, they’ve done a great job.

The Physioblogger holds degrees in both sports science and physiotherapy. He or she is the Director of Functional therapy for FASTER, and holds certifications from FASTER and Gary Gray’s Gray Institute. Look here for a full list of credentials. His or her methods and writings are clearly highly influenced by Gray’s work and the work from FASTER which is to some degree an offshoot of the Gary Gray’s work.

I found the site because I’ve been battling on and off bouts of plantar fasciits and/or Achilles tendon trouble. (I’ve mentioned this stuff in prior posts but my site was hacked and those posts aren’t available right now.)

The Physioblogger holds degrees in both sports science and physiotherapy. He or she is the Director of Functional therapy for FASTER, and holds certifications from FASTER and Gary Gray’s Gray Institute. Look here for a full list of credentials. His or her methods and writings are clearly highly influenced by Gray’s work and the work from FASTER which is to some degree an offshoot of the Gary Gray’s work.

I found the site because I’ve been battling on and off bouts of something like plantar fasciits and/or Achilles tendon trouble. (I’ve mentioned this stuff in prior posts but my site was hacked and those posts aren’t available right now.) Physioblogger’s series on plantar fasciitis starts with Understanding the Root Cause of Plantar Fasciitis. It follows with Plantar Fasciitis: Treatment Strategies – Part I and Part II. The treatment strategies are very comprehensive, covering everything from the toes to the ankles, hips, thoracic spine. Two other articles (Mid-Tarsal Joint Treatment Strategies and 5 Ways to Increase Dorsiflexion) are interesting and may prove helpful in addressing plantar fasciitis.

There’s a lot to look through here and I’m just started. Some of the strategies are beyond my skill set as I’m not a manual therapist. But, I’m getting a lot of good ideas along the way.

NSCA Endurance Clinic Summary: Day 2 (I forgot to summarize the final presentation.)

StandardMaybe I was in a rush to post the Day 2 summary, I’m not sure. I forgot to summarize the final presentation of the day.

Dr. Jeff Matthews: Running Injuries – The Big Picture

- DC, CCSP, CCEP, 1996 USAT National Team, high school track coach

- Primary shock absorber of the body: FOOT PRONATION

- Pronation isn’t a bad thing–it’s supposed to happen.

- Posterior tibialis controls pronation via eccentric contraction

- Secondary shock absorber: knee flexion

- Aches & pains of the leg, foot and toes

- Metatarsalgia

- Pain at the metatarsal phalangeal joint as the heel leaves the ground too early.

- Causes

- limited ankle dorsiflexion

- tight gastrocnemius

- weak digital plantar flexors

- Treatment

- stretch gastroc with straight leg

- increase distal plantar flexor strength

- rigid forefoot in shoes

- decrease stride length & employ heel strike

- I have off and on metatarsalgia. I’m going to work the toe flexors, particularly the flexor hallucis brevis. I’ll use a band.

- Pain at the metatarsal phalangeal joint as the heel leaves the ground too early.

- Hallux limitus and rigidus (aka Turf Toe)

- Dancers and defensive backs get this as a result of doing a lot of stuff on their toes.

- Loaded dorsiflexion of the big toe should be 42 degrees at toe off.

- To check: Sit with knees bent at 90 degrees. Lift toe with finger while foot is flat on the ground. If it’s less than 30 degrees then you’ve got a problem.

- Stretch toe flexors: Pull toe back 20-30x/day.

- Restore joint motion to big toe. I’ve been playing with this stuff quite a bit lately. I’ve got a constantly tight left calf. I’m wondering if restricted toe dorsiflexion is part of the problem.

- I’m not only working to stretch the FHB, but also to strengthen it so my big toe can grip the ground.

- Here’s a good big-toe mobility video:

- Metatarsalgia

- Insertional Achilles tendonitis

- occurs near the base of the AI

- common in high-arched, stiff feet

- common with Haglund’s Deformity.

- Seems I have a bit of this; more along the lines of a bursitis from what I cant tell.

- Strengthen with eccentrics.

- He says “Work on the front of the tendon,” as that’s where the blood flow comes from.

- Achilles Paratendonitis

- He describes this as occurring with an audible squeak or creak–I’ve had that!

- An inflammation of the sheath around the tendon

- Work on the front of the tendon to increase blood flow.

- Achilles non-insertional tendonosis

- degenerative non-inflammatory condition from repeated trauma

- treatment

- rest

- muscle work to stimulate fibrolasts to remodel

- when appropriate, strengthen posterior tibialis and flexor digitorum longus

- How do we strengthen the FDL? Here’s one way:

- Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome aka runner’s knee

- comes from abnormal femoral movement

- hip muscle weakness is the cause; increases with fatigue

- Testing for PFS: 1-leg squat & check for 3 things:

- leaning toward stance leg to maintain balance

- knee caving in

- falling

- Treatment

- retro patellar pain: recruit/strengthen the vastus medialis oblique (VMO)

- stretch hips, foam roll quads, increase hip flexor strength

- IT Band Syndrome (ITBS)

- strengthen hip abductors

- decrease tension on the tendon with soft tissue therapies

- stretch glute max and TFL

- may take 6 weeks (Didn’t take me that long to overcome mine.)

- Check out my post on IT Band issues for more help.

- Popliteus tendonitis

- The popliteous unlocks the knee from the extended position.

- inserts under the IT band and can cause lateral knee pain

- if weak then knee may stay locked and send shock to the back

- Treatment

- Strengthen the popliteous

- soft tissue therapy

- control pronation (probably with foot strengthening drills and more importantly, HIP ABDUCTOR exercises)

- Here’s a video on recruiting and strengthening the popliteous

- Hamstrings

- Hamstring strains have the highest recurrence rate and can take 4 months to resolve

- Semimembranosus protects the medial meniscus during knee flexion

- long head of biceps femoris helps stabilize SI joint and is most frequently injured in runners because of the long lever arm decelerates knee extension

- more proximal the injury the harder to treat

- Treatment

- increase length, strength and flexibility

- evaluate pelvis

- strengthening abs/stabilizing pelvis can position pelvis correctly thus putting hamstrings at proper length

- Low back pain

- Pain causes weakness/looseness

- Internal or external femoral rotation may become problematic.

- Treat hips

- A TFL problem = a glute medius problem. This is huuuuge to me!

- Seems to me that sitting too much is maybe the main problem here.

Good Information: Flexion Inspection (Sitting Is The New Smoking), When to Stop Strength Training (Part of Tapering for a Race), Running Technique

StandardThere are so many knowledgable people out there putting out good information. Here’s a little bit that I’ve found recently.

Kinetic Revolution: Better hip flexion for better running plus overcoming our sitting habit

If you’re a runner or triathlete then you should definitely check out Kinetic Revolution. The author is James Dunne and he’s a rehab and biomechanics expert. His recent post is Flexion Inspection: How Long Do You Sit Down Each Day? He discusses the perils of setting, namely tight hip flexors that inhibit the glutes and thus limit your hip extension. He makes two suggestions:

1. Record Your Time Spent Sitting For 1 Week

This is Claire’s brilliant idea… I had to share it!

Keep a simple diary. Much like a food diary, but recording the time you spend sitting down every day. Every single form of seated activity, from working at a desk to cycling.

If you’re anything like me, the results will be ALARMING.

2. Offset Time Spent In Flexion With Specific Extension Exercises

I’m a realist. I get that much of 21st century living requires sitting – not to mention the leisure activities we engage in. Cycling for instance.

I usually suggest for every two hours spent in a flexion pattern, athletes should get up, and spend 5mins working on extension exercises such as hip flexor stretches and glute activations.

And he explains a hip flexor stretch progression here

I can’t really resist posting this video so we’ll meander away from running technique for a moment. Nilofer Merchant gives a TED talk on this dreadful sitting habit we have. She even suggests that perhaps walking while talking may drive creative thinking:

Sweat Science: When is the ideal time to cease strength training?

If you’re a runner who strength trains (And if you’re a runner, you should strength train.) then this piece from Alex Hutchinson’s Sweat Science column at Runner’s World is very much up your alley. It’s titled When to Stop Strength Training. He discusses research from the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, Here’s the big rock you should know (emphasis is mine):

What you’re looking at is the change in muscular power after resistance training was halted, based on meta-analysis of 103 studies. Note that power is different from absolute strength — power is your ability to deliver large amounts of force in a short period of time, which is often more relevant to athletic performance than plain strength is. And the interesting thing to note is that, 8 to 14 days after stopping, power appears to be a little higher than it was during training, though it’s not statistically significant. (The graph for strength, which I didn’t show, starts declining immediately.)

Speculation aside, if you’re an endurance athlete who includes resistance training in your regimen, you have to eliminate or reduce it at some point before race day. The graph above suggests that one to two weeks in advance might be an interesting time to stop.

Running technique & mirror neurons: Watch and learn

Humans are visually-oritented people. We primarily learn by watching and imitating others around us. (Why did you ever decide to walk? Did someone propose the idea to you? Did you come upon the idea of walking from a book you read? No. You decided to give walking a shot because you looked around and saw a bunch of other people doing it.) Mirror neurons are the specialized structures in our nervous system that enable our learn-by-watching process.

The cool thing is that we can improve our skills by watching other people do things. I’ve watched skiing videos to improve my turns and I’ve watched mountain biking videos to improve my switchback riding. We can improve our running technique the same way.

There are a lot of youtube videos out there on running technique and I’ve found a couple that are fairly informative and somewhat entertaining. These videos are a slightly funny compliation of 80s instructional video, current running analysis and in one clip we see vintage black & white footage of the great Roger Bannister, the man who first broke the 4-minute-mile barrier.

Stuart McGill, Born to Run & Ketogenic Eating

StandardHere’s what I’m into right now:

Stuart McGill

I recently finished Stuart McGill’s Ultimate Back Fitness & Performance. It has definitely contributed to how I view conditioning and care of the spine. For instance:

- I’m very careful to avoid much if any bending or twisting at the lumbar spine.

- According to McGill, the core musculature responds best to endurance-type training, so I now go for time rather than out-and-out strength.

- McGill makes the observation that excellent athletes tend to have a very rigid core–but very mobile hips and shoulders.

- Here are two videos with McGill. The first has McGill discussing several myths regarding low back pain and core strength. In the second video we see demonstrations of three exercises often prescribed by McGill. These are often called the Big 3: the curl up, side plank and bird dog.?

Born to Run

I’m a little late to the party but I recently finished Chris McDougal’s Born to Run. This book has done more than almost anything to push the popularity of minimalist running.

Born to Run is more than a book about running. Much of the book concerns the history and culture of the Tarahumara people who live in the isolated Copper Canyon region of Mexico. Non-runners with any interest in other cultures will find this book very interesting.

The book and author have generated some controversy. Any runner knows about the hot debate over minimalist/barefoot-type running. I won’t go into all that. (For just about the most thorough discussion on minimalist running, you can’t do better than the Sports Scientists dissection of the subject.)

Here are some thoughts on both the book and discussions that have followed:

- The story is quite entertaining. It’s possible that the entertainment value of the book and a subsequent New York Times article from McDougal have somewhat overshadowed some facts.

- Alex Hutchinson who writes the Sweat Science blog for runner’s world describes an interview with McDougal that clashes with later statements from McDougal.

- Hutchinson brings up several points in his response to McDougal’s article titled The Once and Future Way to Run. One is this:

“4. The one part of the article that made me kind of angry was this passage, about McDougall’s visit to the Copper Canyon in Mexico that led to Born to Run:

I was a broken-down, middle-aged, ex-runner when I arrived. Nine months later, I was transformed. After getting rid of my cushioned shoes and adopting the Tarahumaras’ whisper-soft stride, I was able to join them for a 50-mile race through the canyons. I haven’t lost a day of running to injury since.

I actually interviewed McDougall back in 2009, shortly before Born to Run came out. And that’s not the story he told me. Here’s what I wrote then:

Long plagued by an endless series of running injuries, he set out to remake his running form under the guidance of expert mentors, doctors and gurus. He adjusted to flimsier and flimsier shoes, learning to avoid crashing down on his heel with each stride and landing more gently on his midfoot. It was initially successful, and after nine months of blissful training, he achieved the once-unthinkable goal of completing a 50-mile race with the Tarahumara. But soon afterwards, he was felled by a persistent case of plantar fasciitis that lingered for two years. “I thought my technique was Tarahumara pure,” he recalls ruefully, “but I had regressed to my old form.” Now, having re-corrected the “errors” in his running form, he is once again running pain-free.

I’m in New York right now, and won’t be back home until Monday night, otherwise I’d see if I can dig up my actual notes from the interview. But I remember McDougall telling how stressed out he’d been, because he’d spent all this time working on a book about the “right” way to run — but as the publication date loomed ever nearer, he’d been chronically injured for two years. It was only shortly before publication that he was able to get over the injuries and start running again.”

McDougal responds to Hutchinson’s post here and Hutchinson replies back.

Personally this doesn’t do much to bother me or take away from a) a great story that’s told in Born to Run or b) the value and importance of minimalist running. I think it does suggest that McDougal is not a scientist and that the need to create a compelling story may persuade a writer to drift towards a bit of exaggeration.

What’s your take on this back-and-forth?

Ketogenic Diet (high-fat/low-carb/moderate protein intake)

Here’s another party to which I’m a bit late: the high-fat ketogenic diet. In fact, most people who’ve tried it probably abandoned it back in the early 2000s. (I think they should’ve have.) You’ve heard of the Atkins diet. That’s largely what I’m doing now.

In reality, I’m becoming more focused and precise with this type of eating. I switched to a higher-fat diet when I became familiar with the Perfect Health Diet.My current efforts are informed by the Art & Science of Low-Carbohydrate Performance. Jeff Volek, PhD, RD & Stephen Phinney, MD, PhD are the authors. I like their credentials and their experience. To me, it lends weight to their words. Here’s a rundown of the main points of the book:

- Their book is well-referenced and fairly easy to understand.

- They present convincing evidence (to me) in favor of a) greatly reducing carbohydrate and b) greatly increasing fat intake and c) why this strategy can be very effective for athletes.

- How?

- Burning fat for fuel (aka ketogenesis) is a cleaner process.

- Inflammatory stress is lower compared to using carbs for fuel

- You’ll be less damaged from exercise and you’ll recover faster

- You have a nearly limitless supply of fat for fuel compared to a limited supply of glycogen.

- By shifting your metabolism to prefer fat, you’ll avoid bonking.

- Also, by shifting your metabolism to prefer fat you’ll improve your body composition. Besides the aesthetic appeal of a lean physique, if you’re lighter then you’ll have a better ability to produce power. If you’re lighter then you should be able to run and bike faster.

- Endurance athletes who experience GI distress may do very well on the high-fat diet.

I was motivated to dig into this type of eating after I spoke with my former client and friend Mike Piet. He’s moved in the low-carb direction after his friend and accomplished ultra-distance runner Jon Rutherford. Jon’s experience as an athlete who’s increased his performance is described in the Art & Science of Low-Carbohydrate Performance. Thus far, I like the results. I’ll talk more about them as this experiment continues.

Look for Mike Piet’s guest blog post as he describes his very interesting low-carb/high-fat experience during the Savage Man Olympic and half-Iron distance triathlons–done on consecutive days.

Park-to-Park 10 Miler & The IT Band is Fixed!

StandardI ran the Park-to-Park 10 Miler on Labor Day and here’s a brief rundown. Here are the facts:

-

Time: 1:24:27.

-

8:21/mile pace

-

174th out of 534 participants.

-

16th out of 44 men in my age bracket. (I tried to calculate how I did among all men and it was hard to figure out. Looks like I was in about the top ⅓ of the group.)

Nothing spectacular but not too terrible either. I improved on my 2009 time by about a minute-and-a-half. I like that. Other than that, it was very warm and for Denver it was humid. Denver is a hilly town. You may not notice it if you’re driving it but try running 10 miles through town and rarely do you encounter level ground. What follows is more important than any of this.

I first ran this race back in 2009. That was with the beginnings of an Achilles problem that would plague me for about two years. (And I believe the Achilles problem was a symptom of a much bigger collection of issues that had affected me since about 2002.) Since overcoming the Achilles trouble, I’ve run several races including my first marathon last year.

This summer a new problem cropped up in the form of some knee/IT band pain. Would this derail my race? Discussion boards are filled with people bemoaning the fact that they’ve spent years battling IT band pain. What did this mean for me???

I recently discussed the etiology of IT band syndrome and how to address it. (Work on the hip abductors!!) I’ve been a religious ultra-zealot about addressing my hip abductor deficiencies. With much relief and joy, I didn’t feel a bit of pain during the run. IT band pain often strikes during downhill descents. I didn’t feel anything. Nor did I notice anything near the end when I was tired and pushing hard. I’m thrilled to have figured out this issue and to have defeated it in fairly short order.

Excellent Deadlift Instruction From EliteFTS

StandardIn previous posts (which I can’t link to as my site was hacked and those posts are un-retrievable at the moment; I hope to have them available soon.) I put up some videos courtesy of Dave Tate’s EliteFTS.net The So You Think You Can Bench Part I and Part II and Part III; and So You Think You Can Squat Parts I-V (It takes too long to copy and paste those links. If you’re interested, go to Youtube and look them up.) series are fantastic dissections of those two lifts.

Now we’ve got So You Think You Can Deadlift Parts I-V. This series is presented by big-time powerlifting champ Matt Wenning. He’s a lot stronger than you, I, or anyone that we know. He’s also maintained his health and avoided injury while competing at a high level. This series speaks directly to using exercise to expose our weak links so we can make them stronger. If you love to lift and you love the precise breakdown of lifting then you’ll love this series. Here are the vids:

IT Band Syndrome: We Have A Weak Link

Standard“The single most important factor in predicting and possibly treating IT band problems is hip abductor strength.” John Davis, Running Writings

A weak link is found

My last post discussed finding and fixing our weak links. Well, during a trail run I found a weak link and the quest is on to bring it up to a respectable level. At this point I’ve boiled it down to poorly functioning glutes–the glute medius to be specific. Glute dysfunction is fairly common and I’m realizing more and more that I’ve had a good dose of it for quite some time. It’s gotten better but I’ve got to make it better yet. Right now this weak point is causing me some knee pain.

Inside IT band syndrome

Recently, while finishing a long trail run, I began to feel the dreaded symptoms of IT band syndrome (ITBS). Chances are, if you’re a runner then you either have or you will experience this issue too. If you look at the Wikipedia entry on ITBS you realize this is a mysterious ailment that might be caused by a myriad of issues from the feet to the hips, from the muscles to the bones, from too much running or cycling or rowing or dancing or whatever else you might do on one or two legs. Conventional treatment ranges from ice to ultrasound to stretching to orthotics and various pain drugs like ibuprofen. (Do we really think that ITBS was caused by a lack of ibuprofen or an absence ice sitting on our knee?) I want to fix this issue and clarify what’s at work here. Let’s see if I can make some sense.

ITBS symptoms

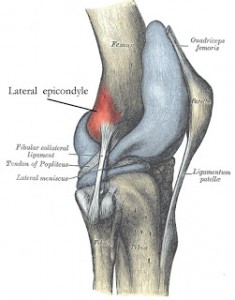

The most typical symptom of ITBS is lateral knee pain, somewhere in the neighborhood of what you see on these two pictures. That’s where the IT or iliotibial band inserts. As is typical, I felt a sudden onset of pain at this site while running downhill. It’s a fairly sharp pain. Knee flexion while stepping down off a step often brings it on. Apparently, ITBS can be felt elsewhere along the IT band.

The research: It’s all about the hip abductors.

I found some superb articles with some very valuable information regarding the root cause(s) of ITBS and how to address the issue. Biomechanical solutions for iliotibial band (IT band) syndrome / ITBS comes from RunningWritings.com. Glutes rehab – recent research and Gluteus medius – evidence based rehab come from Running-physio.com. There is some overlap between these articles and they all refer to quite a bit of important research. If you’re a trainer who’s working with someone who has ITBS or if you’re suffering from ITBS, I strongly suggest you read these articles. I’ve summarized some things but definitely go to the sources for a thorough rundown.

Both sources cite a study from Stanford, and here’s what you need to know:

“Long-distance runners with ITBS have weaker hip abduction strength in the affected leg compared with their unaffected leg and unaffected long-distance runners. Additionally, symptom improvement with a successful return to the pre-injury training program parallels improvement in hip abductor strength.”

Some sources suggest that foot/ankle dysfunction–specifically over-pronation–is at the cause of ITBS rather than hip dysfunction. Irene Davis and others of the University of Delaware studied both the hips and feet/ankles. They stated:

“However, aside from this variable [an increase in rearfoot inversion moment], these results begin to suggest that lower extremity gait mechanics [i.e. foot and ankle] do not change as a result of ITBS. Moreover, the similar results of the current study […] suggest that the aetiology of ITBS is more related to atypical hip and knee mechanics as compared to foot mechanics. Therefore, the current retrospective study provides further evidence linking atypical lower extremity kinematics and ITBS. (Ferber et al.)”

The Running Writings article discusses several other studies that had similar findings to the Stanford study. The writer reached this conclusion:

“At this point, the evidence overwhelmingly points to a biomechanical fault in the abductor muscles of the hip as the root cause for IT band syndrome. Weak or misfiring gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, or tensor fasciae latae muscles are unable to control the adduction of the hip and internal rotation of the knee, leading to abnormal stress and compression on the IT band. This muscular dysfunction manifests as excessive hip adduction and knee internal rotation, both of which increase strain on the iliotibial band and compress it against the fatty tissue between the lateral femoral epicondyle and the IT band proper, causing abnormal stress and damage. But although the pain is coming from the lateral knee, the root of the problem is coming from the hip muscles.”

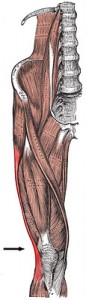

(By the way, the hip abductors of which I speak consist of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus and the tensor fascia latae or TFL. See below.

Here’s something important: Very often the glute medius doesn’t do its share of the work and the TFL does too much work. Therefore it becomes important to condition the glute medius while de-emphasizing TFL activity. The side-lying hip abduction exercise (described below) works particularly well for activating the glute med while minimizing TFL activation.)

The Running Writings piece also says, “a doctoral thesis by Alison Brown at Temple University also investigated (hip abductor) muscle strength in runners with and without ITBS; interestingly, she found no difference in maximal strength, but a significant difference in endurance.”

On a slightly different note, a recent study in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise indicates excessive hip adduction (adduction is the opposite of abduction; If you adduct too much then you’re not abducting enough.) is a precursor to patellofemoral pain or PFP. So again, we see abnormal hip mechanics playing a role in knee pain in runners.

Finally, the Running Writings article does a nice job of dispelling some myths about ITBS, among them the idea of foam rolling and/or stretching the IT Band. I won’t go into all of it but the bottom line is: Don’t bother. The IT band isn’t the problem–it’s the hip abductors! Work on them.

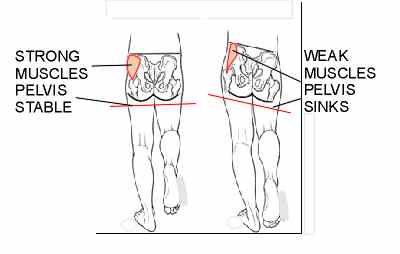

Tredelenburg gait

What happens when those hip abductors fail to do their job? We get what’s called Trendelenburg gait. Here’s a picture of it. Notice the right

hip drops. When that happens the hip muscles on the left are stretched which puts prolonged tension on the IT band. That excess tension may cause pain at the IT band insertion located on the knee. There’s your pain.

Testing the abuductors

Heeding the observation that hip abductor endurance is key to ITBS, I tested that endurance using the old-fashioned, Jane Fonda-style side-lying hip abduction. (I elected to forgo leg warmers.) I got to almost 30 reps on my right leg (the affected side) and the hip was dying. I got to 30 reps on the left leg and with only moderate fatigue. I’ve seen similar performances in several other clients and my wife who also has some ITBS. This all fits in line with what this research found.

The exercises

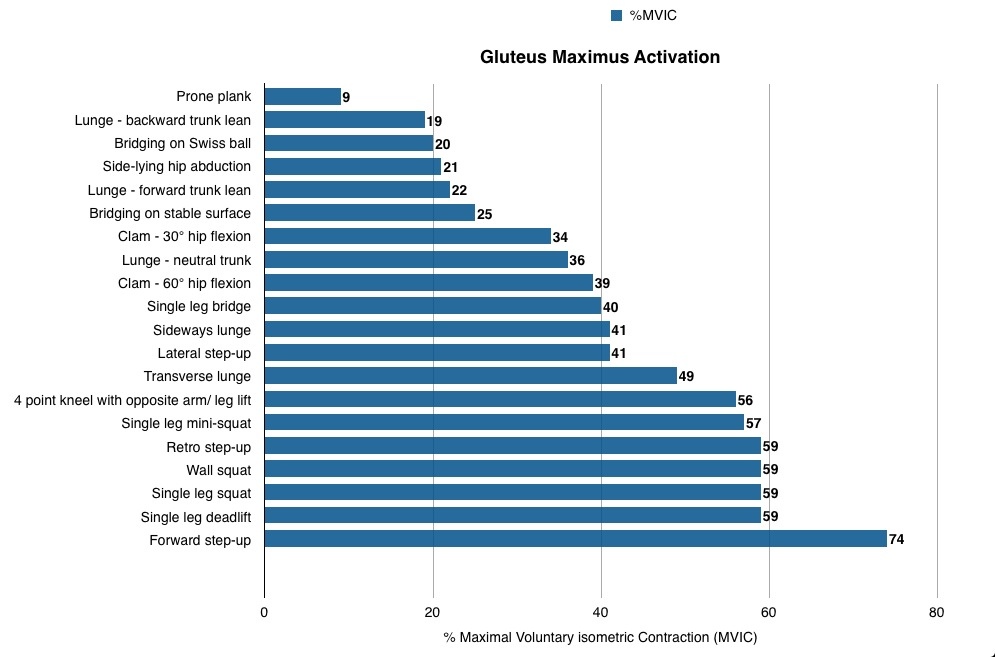

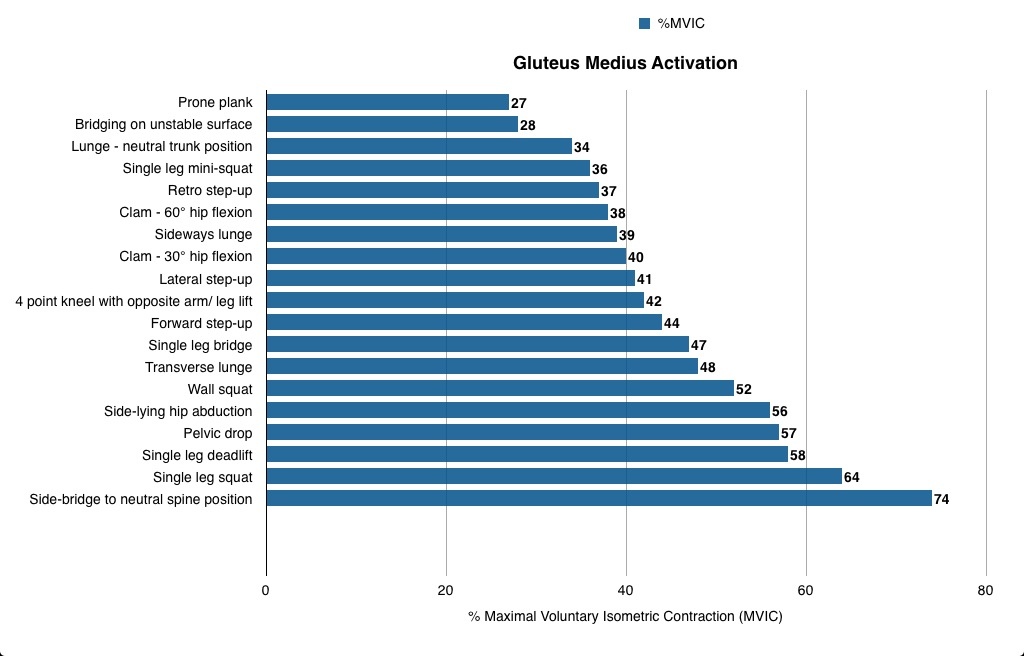

The two articles from RunningPhysio do a great job of discussing a wide variety of exercises that engage the glutes. In Glutes rehab: recent research we see research on the exercises that elicit the most contraction from both glute medius and glute max. Look at the tables below to see which exercises get the most out of these muscles. (I’m not sure exactly how all of these exercises were performed.)

Here’s RuningPhysio’s take on how to apply this information:

Practical application

From the research findings a good programme for runners wanting to target GMed would be starting with single leg mini-squat, side-lying abduction and pelvic drops and progressing to single leg dead lift, single leg squat and side-lying bridge to neutral. For advanced work you could add leg weight to side-lying abduction or combine side plank with upper leg abduction. This set of exercises would start with at least moderate GMed activation and progress to in excess of 70% MVIC. It would contain both functional weight-bearing exercises that are a closer fit to the activity of running, and non-weight bearing activities like side-lying abduction which has been shown to activate GMed without increasing unwanted activity in TFL and anterior hip flexors (McBeth et al. 2012) and has been used successfully to rehab runners with ITBS (Fredericson et al. 2000).

Runners wanting to improve GMax could start with single leg bridge, lunge with neutral trunk and single leg mini-squat and progress to single leg squat, single leg dead lift and forward step up. All of these exercises are ‘closed chain’ single leg activities where the GMax provides power to extend the hip but also works to help stabilise the hip and pelvis. As a result they are fairly functional for runners as GMax has a similar role during running.

In Gluteus Medius: Evidence-based rehab, the writer very wisely discusses differences in what we might call “functional” vs “non-functional” exercises. (This article also describes most of the exercises you’ll want to employ.) Generally, we might say a functional exercise would look like something we do in real life. A 1-leg squat or 1-leg deadlift is an example. These exercises have us standing (weight bearing) and using the whole body in concert. We don’t isolate a muscle in a functional exercise but rather we train a movement pattern and integrate lots of muscles together. In contrast, a non-functional exercise tends to isolate a muscle. The side-lying abduction or side plank are examples of non-functional exercises. These exercises don’t much resemble anything we do during most of our daily activities or sports. That doesn’t mean they don’t have value though, and the article does a nice job of discussing this issue. The article states:

“Closing thought, from the research I’ve read and patients I’ve seen, a combination of both functional weight bearing and less functional (sidelying) exercises is most likely to be effective in glutes rehab.”

My process

Like I said, my right glute med is indeed easier to exhaust than my left. I figure though that I should work both sides with a little extra work on the right. I’ve been doing lots of the side leg raises and side planks. I can’t yet do a good side plank while abducting the top leg. That’s a tough one. It’s one to shoot for in the future. I’m also doing a lot of band walks. I don’t loop the band around my ankles though, I loop it around my feet. This study determined that placing the band around the feet recruits more glutes and less TFL. These are sort of the non-functional exercises that I do pre-workout or first thing in the morning.

Pre-workout or throughout the day:

- side-lying hip abduction: 2-3 sets x 10-20 reps. I go to exertion.

- side planks: 2-3 sets x 10-20 seconds

- band walks: I side shuffle as well as walk forwards and backwards. I go to exertion.

- Hip hikes: Easy to do. This movement has you lifting the pelvis away from the Trendelenburg gait pattern.

Functional/main exercises:

-

1-leg squat: 3 x 8-15 reps. I recently used a kettlebell in the arm opposite my stance leg. I focus on keeping my pelvis level, knees somewhat apart and I don’t let my non-stance side hip drop which is very important. I also throw several reps in randomly throughout the day.

-

1-leg deadlift 3 x 8-15 reps: I often hold one or two kettlebells, dumbbells or a barbell.

-

Off-set step up: 3 x 6-12 reps use a knee-high plyo box for this. I hold a dumbbell on the side opposite my stance leg. I drive up powerfully with the stance leg then do my best to control my descent back down. I don’t plummet back down uncontrolled.

-

ice skaters: 3 x 12-20 reps. This is a power exercise in which I drive side to side in an explosive manner. There’s no way to do this without using the glute medius.

-

1-arm carries/farmer walks: I carry a kettlebell in one hand and walk. Very functional and simple to do.

These exercises do a great job of conditioning our movement sling system. Read here and here to learn more about these systems of muscles that work together as we move.

Where’s Your Weak Link? Using Exercise to Expose Weakness – Part I

StandardOne big concept is on my mind and it’s been expressed by several experts that I look up to. In his book Movement, Gray Cook says “True champions will spend more time bringing up weaknesses than demonstrating strength.” The great powerlifting coach Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell says, “The Westside program is all about finding where you are weak and making it strong. Your weaknesses will hold you back. Kelly Starrett discusses the idea of “making the invisible visible.” With this statement he suggests we can use exercise to expose movement problems. (He talks about this concept here, here and here.) What does all this mean?

All these guys are telling us that rather than going to the gym and doing fun stuff that we’re already good at and simply making our strengths stronger (taking the easy route, really) rather we should find our weaknesses and work like hell to bring them up to speed.

A slightly different paradigm

I think most of us have an equation in our head regarding exercise. It might look like this:

I exercise → I get stronger.

(BTW, the word “strong” doesn’t just mean muscular strength. We can get stronger at swimming, biking, driving a golf ball, carrying bags of mulch, etc. “Stronger” means to improve an ability.)

There might be a few more dots to connect between those statements though. With regard to the earlier statements about weaknesses and making the invisible visible (i.e. make hidden weaknesses visible), we might see the equation thus:

I exercise → I expose weaknesses/pain/poor movement → I correct/improve my weaknesses and poor movement →I get stronger.

What often happens is that we find an exercise that we really like and at which we’re very strong. We really like that exercise! We do it and we demonstrate to ourselves (and let’s face it, others in the gym) how strong and able we are. Therefore our already well-developed ability gets stronger.

In contrast, I think a lot of us have discovered exercises that we really don’t like. The movement pattern feels awkward, painful or somehow asymmetrical or unbalanced. We have a poor ability to execute the exercise. In other words, we’re weak at this particular movement. We don’t do it well and we know it. Thus we rarely if ever explore this particular exercise. What happens? We probably get weaker and weaker at it.

So while something we’re already fairly good at gets better, a glaring weakness gets weaker. And what do we know about chains and weak links? At some point that weak link (poor movement pattern) is going to cause us a problem if it isn’t already. We may not even know how strong we could be if we fixed our weakness.

My rule of thumb is: “If it’s really difficult to do and you don’t like doing it, then you probably need to do a whole lot of it.”

My experience

A lot of my clients have movement problems and various aches and pains. Their weaknesses are often rooted in a forgotten ability to move properly and maintain their joints in proper position. We frequently need to dial back the exercise intensity and simply work on slow, proper, mindful movement. Sometimes this requires a frustrating level of concentration. It gets difficult. It isn’t always fun. This frustration may lead a client to say ” I just want to work out! I don’t want to think!” In other words, he or she want to revert to their hold habits, ignore their movement shortcomings and do what they’re already good at.

This is an important fork in the road. If a client chooses to continue to focus and do the hard work of correcting bad habits–to improve their true weaknesses–then he or she will almost certainly start to see lasting improvement in the near future. This client and I will likely have a long, productive and happy relationship. On the other hand, we have another type of client. He or she balks at the first sign of difficulty, ignores and avoids weaknesses, and in essence chooses to tread water and only marginally strengthen their limited strengths. He or she has picked an easy but limited route. In this case, our relationship is thankfully short.

The big picture

I’m going to go into some specifics in the next post, but for now I’d like you to consider the idea that the real way to get stronger is to seek out and wallow in your pathetic weaknesses. If you think you don’t have any, then add weight, reps, range of motion and/or speed to see if things start to come apart. Recognize where you start to fail and dedicate yourself to working on those weaknesses.

Interesting and Informative Information: Fat Isn’t So Bad, Skimpy Research on Injury Prevention in Runners

StandardRead this! Learn things!

What if bad fat isn’t so bad?

“Ronald Krauss, M.D., won’t say saturated fats are good for you. ‘But,’ he concedes, ‘we don’t have convincing evidence that they’re bad, either.'”

I’ve written here that I’ve been persuaded that not only is fat good for us, that “bad” saturated fat is also at the very least not as bad for us as we’ve been led to believe. I found another article to further support my thoughts. What if fat isn’t so bad? is a 2007 article from NBC News. In it, we get a good dissection of the various flawed studies by which we’ve arrived at the idea that fat–particularly saturated fat–is pure evil.

The article discusses among other things Ancel Keys’s landmark Seven-Countries Study from 1970. This study did more to advance the fat/cholesterol/heart disease link than anything else around. This study went on to frame our current low-fat guidelines. Seems the conclusions that were drawn were quite inaccurate. From the article (emphasis is mine):

“The first scientific indictment of saturated fat came in 1953. That’s the year a physiologist named Ancel Keys, Ph.D., published a highly influential paper titled “Atherosclerosis, a Problem in Newer Public Health.” Keys wrote that while the total death rate in the United States was declining, the number of deaths due to heart disease was steadily climbing. And to explain why, he presented a comparison of fat intake and heart disease mortality in six countries: the United States, Canada, Australia, England, Italy, and Japan.

The Americans ate the most fat and had the greatest number of deaths from heart disease; the Japanese ate the least fat and had the fewest deaths from heart disease. The other countries fell neatly in between. The higher the fat intake, according to national diet surveys, the higher the rate of heart disease. And vice versa. Keys called this correlation a “remarkable relationship” and began to publicly hypothesize that consumption of fat causes heart disease. This became known as the diet-heart hypothesis.

At the time, plenty of scientists were skeptical of Keys’s assertions. One such critic was Jacob Yerushalmy, Ph.D., founder of the biostatistics graduate program at the University of California at Berkeley. In a 1957 paper, Yerushalmy pointed out that while data from the six countries Keys examined seemed to support the diet-heart hypothesis, statistics were actually available for 22 countries. And when all 22 were analyzed, the apparent link between fat consumption and heart disease disappeared. For example, the death rate from heart disease in Finland was 24 times that of Mexico, even though fat-consumption rates in the two nations were similar.”

The large-scale Women’s Health Initiative is discussed:

“We’ve spent billions of our tax dollars trying to prove the diet-heart hypothesis. Yet study after study has failed to provide definitive evidence that saturated-fat intake leads to heart disease. The most recent example is the Women’s Health Initiative, the government’s largest and most expensive ($725 million) diet study yet. The results, published last year, show that a diet low in total fat and saturated fat had no impact in reducing heart-disease and stroke rates in some 20,000 women who had adhered to the regimen for an average of 8 years.”

Several other studies are discussed. The comment from the article on these studies is this:

“These four studies, even though they have serious flaws and are tiny compared with the Women’s Health Initiative, are often cited as definitive proof that saturated fats cause heart disease. Many other more recent trials cast doubt on the diet-heart hypothesis. These studies should be considered in the context of all the other research.”

The article goes on to discuss the subtle differences between the types of LDL or “bad” cholesterol. Seems that all LDLs aren’t created equally:

“But there’s more to this story: In 1980, Dr. Krauss and his colleagues discovered that LDL cholesterol is far from the simple “bad” particle it’s commonly thought to be. It actually comes in a series of different sizes, known as subfractions. Some LDL subfractions are large and fluffy. Others are small and dense. This distinction is important.

A decade ago, Canadian researchers reported that men with the highest number of small, dense LDL subfractions had four times the risk of developing clogged arteries than those with the fewest. Yet they found no such association for the large, fluffy particles. These findings were confirmed in subsequent studies.

Link to heart disease

Now here’s the saturated-fat connection: Dr. Krauss found that when people replace the carbohydrates in their diet with fat — saturated or unsaturated — the number of small, dense LDL particles decreases. This leads to the highly counterintuitive notion that replacing your breakfast cereal with eggs and bacon could actually reduce your risk of heart disease.”

In much of the medical community, this talk of fat being healthy (or at least not un-healthy) is heresy. There seems to be a strong bias against openly discussing evidence to the contrary.:

“Take, for example, a 2004 Harvard University study of older women with heart disease. Researchers found that the more saturated fat these women consumed, the less likely it was their condition would worsen. Lead study author Dariush Mozaffarian, Ph.D., an assistant professor at Harvard’s school of public health, recalls that before the paper was published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, he encountered formidable politics from other journals.

“‘In the nutrition field, it’s very difficult to get something published that goes against established dogma,’ says Mozaffarian. ‘The dogma says that saturated fat is harmful, but that is not based, to me, on unequivocal evidence.’ Mozaffarian says he believes it’s critical that scientists remain open minded. ‘Our finding was surprising to us. And when there’s a discovery that goes against what’s established, it shouldn’t be suppressed but rather disseminated and explored as much as possible.'”

Go here to read the full article.

Injury prevention in runners – “skimpy research”

The smart people at Running-Physio have done a good job of summarizing a research review of studies looking into injury prevention in runners. In all, 32 studies involving 24,066 participants were examined. The relationship between injury and running frequency, volume, intensity and duration were examined. The results? I’ll let the writers tell you;

“Regular followers of RunningPhysio will know of the ongoing debate we have with those staunch supporters of research who insist we must be evidence based. Surely this shows us just how unhelpful research can be in reality – over 30 studies, involving 24,000 runners and no firm conclusions on injury prevention! No wonder Verhangen (2012) described it as “skimpy published research” and went on to conclude,

‘Specifically for novice runners knowledge on the prevention of running injuries is practically non-existent.’

Nielsen et al. isn’t the first review of its kind in this field – a Cochrane Review in 2001 reached a very similar outcome and was updated in 2011 with equally negative conclusions; Yeung, Yeung and Gillepsie (2011) completed a review of 25 studies, including over 30,000 particpants and concluded,

‘Overall, the evidence base for the effectiveness of interventions to reduce soft-tissue injury after intensive running is very weak.’

They go on to make the very wise observation that, “More attention should be paid to changes in training charactisitcs rather than the characteristics themselves.” Based on their reading of the research review, Running-Physio makes the following suggestions:

Novice runners should be especially cautious with increasing volume or intensity of training.

Increase in weekly mileage should be done gradually. The higher the weekly mileage the more caution needs to be applied in increasing this distance. Running expert Hal Higdon talks about runners having a ‘breaking point’ – a weekly mileage above which they start to develop injuries. For every runner this is different but with experience you can find your breaking point and aim to work below it. A gradual increase in mileage helps avoid crossing this point and picking up an injury.

Changes in intensity of training should be added in isolation, rather than combined with increase in distance. Be cautious when adding interval training or hill work and use each training session for its specific goal (i.e.long slow runs at an appropriately slow pace).

Be aware of signs of injury – look out for persistent or severe pain, swelling, restricted movement or sensations of giving way.

Use rest sensibly – don’t be afraid to rest or replace running with cross training when your body needs it.

Seek help – the right GP, Physio or health care professional can make a real difference!

Something I observe here is that we’re often looking for the (training variable) that causes the one thing (an injury). In reality, it’s typically many variables (some of them unseen) that bring on an injury. Also, nowhere in the article or the research is the discussion of running technique. I would think that how someone runs probably has a big effect on whether or not he or she becomes injured. I’ve mentioned previously that where the foot lands in relation to one’s center of mass is quite important as it pertains to impact and running efficiency. I’d be interested in an analysis of the foot placement (and stride length and cadence) in the role of injury.