If you’re a fitness or injury rehab professional then you probably recognize the name Gary Gray. His name is often associated with the concept of “functional” training.

In short, Gray realized early in his career that the body works in a very different way from the way he was taught. He saw that the body was far less a collection of individual pieces and is actually tremendously interconnected. What happens at one joint and one area of the body has an effect throughout the rest of the body. He recognized that muscles typically move eccentrically (lengthen) before they move concentrically (shorten). He saw that all of our movement is affected by gravity, mass and momentum. He realized that most of the time we need to be strong and mobile while standing up as opposed to sitting on something like a weight-stack machine. He also noticed that we do a lot of work on one foot as we walk, step, and run.

(I learned a traditional model of anatomy and movement and I agree very much with Gray that real-life movement and muscle function happen very differently from what’s taught in lots of text books.)

The concept of functional training has spawned endless discussion. Ask 10 different trainers or coaches what functional training is and you’ll probably get 10 different answers. Some associate functional training with doing everything on a BOSU, stability ball or only on one leg. I think it’s a little more complicated. In the end, isn’t all training supposed to be functional? When would we seek out non-functional or dysfunctional training?

These are the characteristics of functional training as I see them:

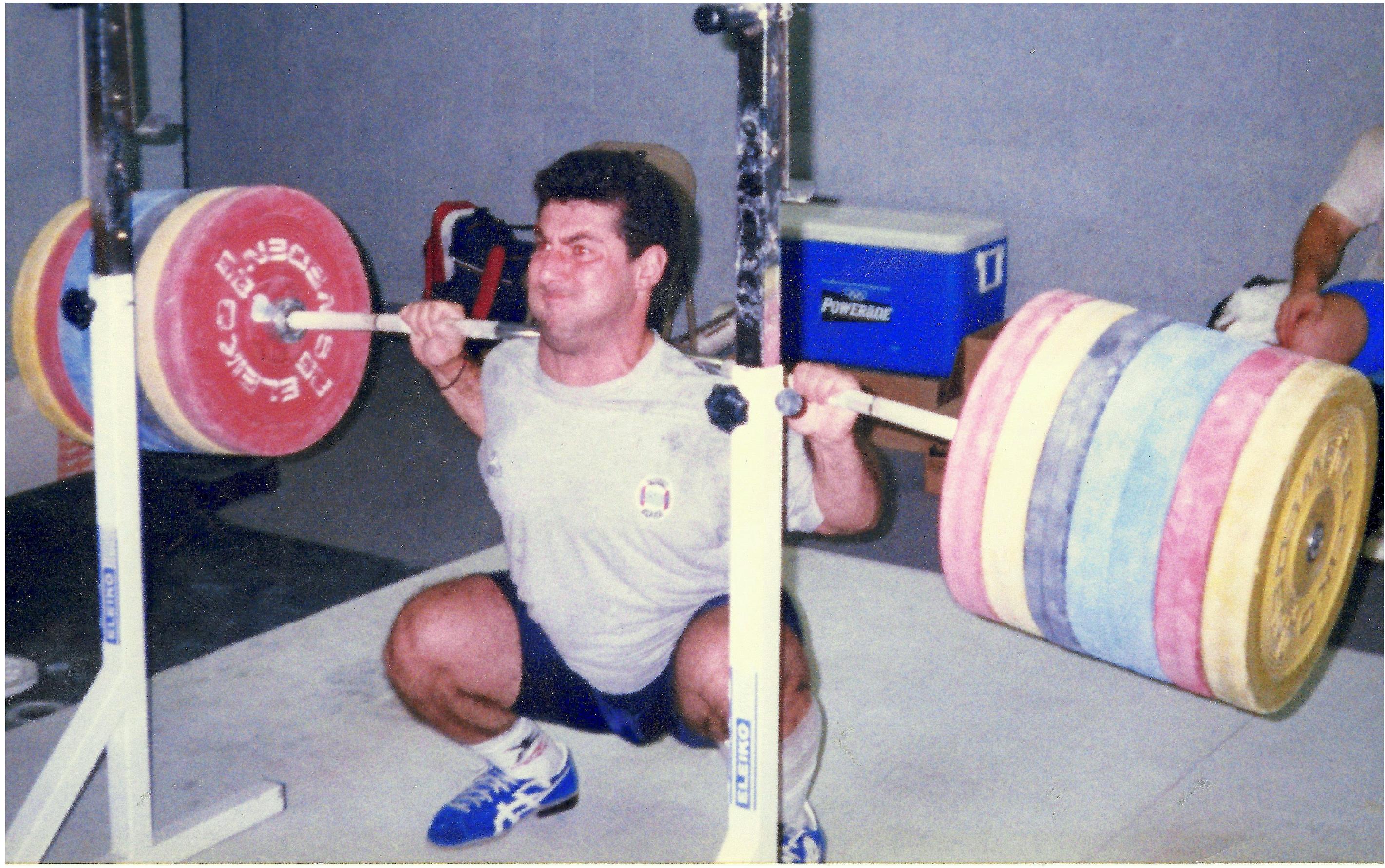

These runners are primarily moving forward but rotation and side-to-side movement is clearly visible.

3D/tri-plane mobility and stability

We move in three planes. We move in the saggital plane or front to back, the frontal plane or side-to-side, and the transverse plane or left/right rotation. Not only do we move in those planes but we must be able to stabilize our bodies as forces act on us in these three planes. Certain movements, sports or activities may demand more from us in one of these planes and less in another. For instance cycling is very saggital plane dominant. There’s very little transverse or frontal plane movement when we ride a bike. In contrast, tennis puts features a lot of work in all three planes. Functional training recognizes these needs and trains them accordingly.

Joints and limbs are integrated during movement.

If we look at the body during typical real-life movement we see all the joints and limbs move together in an integrated fashion. Walking, stepping out of a car, picking up an object from the ground, throwing a ball, kicking a ball and standing up from a chair utilize all the joints limbs and muscles to accomplish the task. Gray calls these types of movements “authentic.” Functional training recognizes and favors this integrated movement process over isolated or “inauthentic” movement.

Joints and limbs are rarely if ever isolated.

Our bodies are integrated systems. In real life, we rarely move just one joint. We should train accordingly.

In contrast to the integrated movement concept, we have exercises that isolate the limbs and joints. Many gym exercises (particularly machine-based exercises) are of an isolated nature. These exercises rarely have any similarity to typical human movement. In a leg extension for example, the user typically sits down with his or her feet off the ground and then flexes and extends the knee in isolation to perform the exercise. No other muscles or joints are moved during this exercise. Now, I ask you, when was the last time you needed strong quads–but not glutes, hamstrings and other leg and trunk muscles–while seated and your feet not touching the floor? This just doesn’t happen outside of a gym.

Muscles work eccentrically before they work concentrically.

This means muscles lengthen before they shorten. For instance, if we prepare to jump into the air then must perform a partial squat before we leave the ground. When this happens we get a lengthening of the quads, hamstrings, glutes, adductors, calves; and if we swing the arms back then we lengthen the front deltoids, the biceps and various other muscles. These muscles then rapidly shorten in the opposite direction as we jump. Similarly in the overhead throw, the thrower draws back the ball and lengthens the abs, triceps, pecs, lats, hip flexors and others before launching the ball.

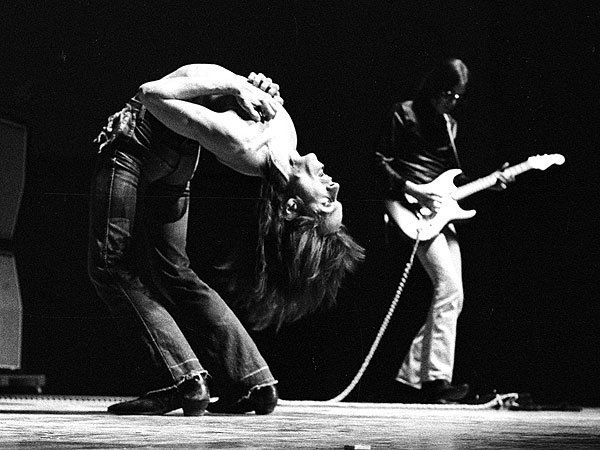

Iggy Pop is showing us both eccentric muscle lengthening (the whole front of his body) AND amazing end-range control.

This lengthen/contraction cycle (Gray often calls it “load to explode”) happens constantly throughout the day during nearly all activities. Most often it happens as our bodies manage gravitational forces as we interact with the ground. This eccentric-first model is functional in terms of typical human movement. It stands in contrast to a lot of anatomy and physiology teaching which emphasizes the concentric contraction only.

End-range control

The end-range of motion is somewhere near the furthest edge of where we can move. Once we get there we often reverse our movement and go back in the direction where we started. (Gary Gray calls this the “transformation zone.”)

This end-range is where a lot of injuries occur. We’re vulnerable at the end-range but clearly we go there sometimes even if we’re not athletes. If we have the flexibility to get there but we lack control and strength in that range then we may be in trouble. Functional training creates conditions where we go to the end range under control and learn to work there. For a lot more on end-range matters, check out Todd Hargrove’s article.

The lunge stance by the fencer on the right is a good example of an end-range of movement requirement. (Photo by Hannah Johnston/Getty Images) ORG XMIT: 148073293

Most exercises are done standing.

Typically we need to be strong and/or powerful when we’re standing on one or two feet. It’s rare that we need to exert much muscular force when we’re sitting or lying down. For this reason, most functional training is done standing.

Perhaps more specifically, functional training is often conducted with the body in the position of the required task. Life and athletic competition may require us to get into any number of positions and postures.

Though most functional training is done while standing, I think there’s a lot of use in doing things on the ground in quadriped, on our side, and lying on our back or stomach. For that matter, just going from the ground to standing up may be very functional for a lot of people.

Externally directed vs. internally directed

I’ve discussed external cueing vs internal cueing as it pertains to coaching movement. External cueing directs the athlete to affect his or her environment. Internal cueing directs the focus internally into the body. An external cue might be “Step toward the target,” “Reach to the ceiling,” “Reach right/left,” “Reach down,” “Push,” and “Pull,” are examples of externally directed or task-oriented directions. Internal cues include “Squeeze the muscle,” “Contract the quads,” “Abduct the arm,” “Extend the leg,” “Tighten the abs,” are examples of internal cues. Functional training favors external cues (task-oriented) over internal cues, (Though I’ve found internal cues to be essential at times.) When using external cues we seem to get a full-body reaction and we can see as Gray terms it “authentic” movement. In other words we can observe how the person chooses to move and how their nervous system organizes the movement. With external cues we can see a client/patient react rather than perform for us.

(For more on internal/external cueing, this article from Bret Contreras may interest you.)

Energy-system specific

Thus far the functional training criteria I’ve listed has pertained only to movement. But if we really want to be comprehensive in our functional conditioning then we need to include a focus on the energy system(s) to be used during something like an athletic activity.

Let’s take distance running for example. It’s mainly a single-leg activity so we might want to perform one-leg squats of some sort and/or one-leg hops and jumps. So we have our exercises. With regard to the energy system, it’s the aerobic system that primarily drives distance running. With that in mind we probably want to perform the exercises while that system is up and running full-bore. That might mean doing very high reps (2 minutes or more) of our exercises. We could also run for a while, do one or more of our exercises, run more, do exercises and repeat for some duration. Or we could do several exercises in a row such that it takes several minutes to complete a circuit.

(I give further ideas for energy system conditioning for skiing here.)

Did I miss anything?

There are my thoughts and observations on what constitutes functional training. What do you think? Can you add anything else?