Science and it’s use by industry are the topics of two recent articles. One story looks at the food industry’s use of science to hook us on their products. Another article shows us how the pharmaceutical industry does its best to hide science from us to… well… hook us on their products.

Junk Science

“With production costs trimmed and profits coming in, the next question was how to expand the franchise, which they did by turning to one of the cardinal rules in processed food: When in doubt, add sugar.”– The Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk Food, NY Times

If you haven’t read it yet then I highly recommend you check out a recent article from the New York Times Magazine titled The Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk Food. It’s a little long but well worth the read. Lest anyone think

that giving up junk food is all about willpower, this article might change your mind.

We get an in-depth look at the very determined scientific efforts by processed food companies (General Mills, Frito-Lay, Cadbury Schweppes for example) to create food that stimulates us to an unbelievable degree. The motive of course is to get us to buy and consume what most of us know to be poison filth. The writer has interviewed hundreds of current or former food scientists, marketers and CEOs to get an inside look at how all this works.

These companies’ efforts include laboratory research into such things as “mouth feel” or how a snack feels in our mouths. Based on the replies of focus groups, food engineers may manipulate a snack in a myriad of ways. Degree of crunch, softness, creaminess, thickness, puffiness, smoothness, gumminess–all sorts of sensations and combinations of sensations are carefully manipulated to help create the ultimate user experience.

Closely associated to mouth feel is the “bliss point.” Just what is a bliss point? It’s sort of a holy grail for junk food. It’s a concept that arose from the observation that very strong flavors may be enjoyable but quickly help tell our brain to stop eating. Meanwhile bland food may be unexciting but we can eat loads of it without feeling the need to stop. The bliss point is the fine combination of the two that leads to a snack that tastes amazing but also manages to sidestep our brain’s wiring so that we’ll eat more and more. From the article:

This contradiction is known as “sensory-specific satiety.” In lay terms, it is the tendency for big, distinct flavors to overwhelm the brain, which responds by depressing your desire to have more. Sensory-specific satiety also became a guiding principle for the processed-food industry. The biggest hits — be they Coca-Cola or Doritos — owe their success to complex formulas that pique the taste buds enough to be alluring but don’t have a distinct, overriding single flavor that tells the brain to stop eating.

Thirty-two years after he began experimenting with the bliss point, Moskowitz got the call from Cadbury Schweppes asking him to create a good line extension for Dr Pepper. I spent an afternoon in his White Plains offices as he and his vice president for research, Michele Reisner, walked me through the Dr Pepper campaign. Cadbury wanted its new flavor to have cherry and vanilla on top of the basic Dr Pepper taste. Thus, there were three main components to play with. A sweet cherry flavoring, a sweet vanilla flavoring and a sweet syrup known as “Dr Pepper flavoring.”

Finding the bliss point required the preparation of 61 subtly distinct formulas — 31 for the regular version and 30 for diet. The formulas were then subjected to 3,904 tastings organized in Los Angeles, Dallas, Chicago and Philadelphia. The Dr Pepper tasters began working through their samples, resting five minutes between each sip to restore their taste buds. After each sample, they gave numerically ranked answers to a set of questions: How much did they like it overall? How strong is the taste? How do they feel about the taste? How would they describe the quality of this product? How likely would they be to purchase this product?

All this is outrageous in terms of the lengths to which food companies go to sell us garbage. It shouldn’t be surprising though. Food companies are in a high-stakes game. They need to sell stuff. Fortunately, because of information like this, these companies and their products may come under the same scrutiny the tobacco industry experienced a few years ago. What else can I say? I think all this is highly fascinating. Read up!

The medical wool over our eyes

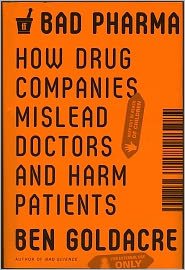

So the junk-food industry loves science because it helps them create products that we love to death. In sort of the opposite direction, the pharmaceutical industry isn’t quite so interested in paying attention to science. Truth About Your Medicine: Ben Goldacre on How to Reform the Pharmaceutical Industry comes form the Daily Beast. In it, Ben Goldacre tells us how the drug companies choose to ignore, diminish or squash unflattering research into their products. He writes:

“The systematic review evidence on missing results shows that, for the treatments we use today, our best estimate is that half of all trials haven’t been published; trials with flattering results are twice as likely to be shared. This is an issue with academic trials, as well as industry sponsored research.”

So what he’s saying is that much of the evidence and scientific analysis of drugs isn’t available for anyone to read. It hasn’t been published. He further states:

“This presents such huge problems for informed decision making, which are obvious to even the most casual observer, and the issue of missing trials could not possibly survive informed public scrutiny. This is why a battle has been waged to pretend that the problem doesn’t exist, helped along by a series of “fake fixes” that have delivered little more than false reassurance.”

The article also links to the transcript of a recent live chat with Goldacre on this topic.

Ben Goldacre is a fairly interesting guy. I wrote about his previous book Bad Science. He makes laudable efforts to both demystify science and call on the carpet questionable industries such as complimentary/alternative medicine to the drug companies. His new book is Bad Pharma. Sounds interesting.