- Internal cue: The athlete focuses on his/her body parts and how they move.

- External cue: The athlete focuses on affecting something in his/her environment. He/she focuses on the outcome of his/her movement.

Below are some examples of internal and external cues from an NSCA article titled What We Say Matters, Part I.

(What We Say Matters, Part II is also very interesting. I won’t discuss the whole thing but it goes into feedback frequency, or how much information coaches should give athletes while they’re learning a new skill. Turns out a good bit less feedback is better than giving feedback 100% of the time. Coaches and trainers should definitely read it. On to the internal/external cues.)

Table 1provides examples of internal versus external focus cues for different movements and note that analogies can be considered external cues.

|

Internal Cue |

External Cue |

| Sprinting: Acceleration |

- Extend your hip (knee)

- Activate your quad (glute)

- Stomach tight

|

- Drive the ground away

- Explode off the ground

- Brace up

|

| Change of Direction |

- Hips down

- Feet wide

- Drive through big toe

|

- Roof over head

- Train tracks or wide base

- Push the ground away

|

| Jumping |

- Explode through hips

- Snap through ankles

- Drive hips through head

|

- Touch the sky

- Snap the ground away

- Drive belt buckle up

|

| Olympic Lifting: Snatch |

- Drive feet through ground

- Drive chest to ceiling

- Snap hips through the bar

- Drive feet through ground

- Drive chest to ceiling

- Snap hips through the bar

|

- Push the ground away

- Drive/jump vertical

- Snap bar to ceiling

- Snap and drop under bar

|

Which is best? Internal or External?

The article cites research that demonstrates internal cues to be more effective than external cues. More evidence comes in an article from Strength and Conditioning Research (a great resource) titled How Much Difference Do External Cues Make? The following studies are cited and they’re summarized:

- Marchant (2009) – the researchers found that an external attentional focus led to greater force and torque during isokinetic elbow flexion movements while simultaneously decreasing muscle activation as measured by EMG.

- Porter (2010) – the researchers found that directing attention toward jumping as far past the starting line as possible had a much greater effect at increasing broad jump distance compared to focusing attention on extending the knees as fast as possible.

- Wulf (2010) – the researchers found that an external focus led to increased jump height with simultaneously lower EMG activity compared to an internal focus of attention.

- Wu (2012) – the researchers found that an external attentional focus let to increased broad jump distances despite not affecting peak force production compared to an internal attentional focus.

- Makaruk (2012) – the researchers found that 9 weeks of plyometric training with an external focus led to greater standing long jump and countermovement jump (but not drop jump) performance compared to training with an internal focus.

- Porter (2012) – the researchers found that an external focus far away from the body led to greater results than an internal focus or an external focus near the body in terms of standing long jump performance.

“So in general, the main factor that is associated with external focus is an increase in performance. Also, there may be a tendency for reduced EMG activity at the same time. This is interesting, as it may be a mirror image of what happens with internal focus.”

The reference to reduced EMG means that with an external focus, more muscles are actually relaxed during the movement. The benefit to that is that the muscles acting in opposition to the movement are more relaxed, thus allowing for better movement. If too many muscles are contracted then we may move slow.

How does an external rather than internal focus result in superior outcomes? The NSCA article cites work by Dr. Gabrielle Wulf, Director, Motor Performance and Learning Laboratory at UNLV:

“Wulf et al. (17) defined the hypothesis, stating that focusing on body movements (i.e. internal) increases consciousness and ‘constrains the motor system by interfering with automatic motor control process that would ‘normally’ regulate the movement,’ and therefore by focusing on the movement outcome (i.e., external) allows the ‘motor system to more naturally self-organize, unconstrained by the interference caused by conscious control attempts.’”

From other research by Wulf in another article:

“Wulf et al. (2001) explained this benefit of an external focus of attention by postulating the ‘constrained action hypothesis’. According to this view, individuals who utilize an internal focus constrain or ‘freeze”’their motor system by consciously attempting to control it. This also seems to occur when individuals are not given attentional focus instructions (2). In contrast, an external focus promotes the use of more automatic control processes, thereby enhancing performance and learning (3,5).”

To me this suggests that the external cueing allows us to tap into reflexes, reactions and movements controlled by the autonomic nervous system. I think any athlete has experienced the situation where we think too much and our performance falters. We think very hard about the individual components of what we’re trying to do and the result is we don’t ski well, we don’t drive a golf ball well, we miss an Olympic lift. In contrast, we’ve been in that “zone” where things just happen. We don’t think, we do. Everything is coordinated and we’re barely aware of what we’re doing. It seems that the external cues are the best way to get to our ideal way of moving.

Is there a place for internal cues?

So the research tells us that external cues are superior to internal cues. Does that mean we should do away with all internal cues? That issue has been discussed in an article by Bret Contreras titled What Types of Cues Should Trainers and Coaches Provide? and an article by Sam Lahey titled the Science and Applications of Coaching Cues. They’re both in agreement that internal cues are sometimes the best way to go when coaching. As often happens, the coaches in the field have some disagreement with researchers.

Contreras does a very good job in discussing his observations of when internal cues might be superior to external cues, particularly when it comes to getting an athlete or client to feel his or her glutes. This is from his article:

“When I train beginner clients, it takes me considerable time to get their lumbpelvic-hip complex working ideally during squats, deadlifts, back extensions, and glute bridges. In my opinion, external cueing is not ideal for improving form in the most rapid manner possible. My belief is that internal cueing will get the individual to where you want them to be in a much more efficient manner.

This applies to preventing lumbar flexion in a deadlift, preventing valgus collapse in a squat, or preventing lumbar hyperextension and anterior pelvic tilt in a back extension or hip thrust.

1) Palpating different regions of their body to make them aware of the various parts involved and what those parts are doing,

3) Having them stop approximately 3/4 the way up on a hip thrust and practicing anterior and posterior pelvic tilt so they can understand how to prevent anterior tilt from occuring,

5) Being ‘hands-on’ during their performance and manually helping place their pelvis in proper position, manually setting the core in neutral, manually pushing the hips upward to ensure full ROM is reached, and poking the glutes to make sure they’re on and the hammies to make sure they’re not overly activated, and

I don’t believe that this heavily ‘internal’ approach can be improved-upon by a purely external cueing approach.”

I tend to agree with Contreras. I’ve often found that I need to bring awareness to one piece of the overall movement puzzle (glutes are the best example). I want clients particularly aware of glute contraction at the very top of a squat, deadlift or kettlebell swing. Contracting the glutes tightly at the top of these movements is important for keeping the pelvis and lumbar spine in good, safe position and for getting the most “oomph” into the lift. Before I teach these exercises, I want the client to know what it feels like to squeeze their glutes. I simply want them to know what the glute contracting feels like. I don’t need them to move fast or lift heavy. In this case, an internal cue seems to be the best way to go. I’m not sure of a more effective cue than saying “Squeeze your butt as tight as possible,” when I want to make someone aware of their glutes.

(Though now that I think about it, “Squeeze a quarter between your butt cheeks as tight as possible” might actually be an external cue that would work very well.)

Contreras also cites the cues “chest up” and “knees out” during the squat as simple, effective and commonly used internal cues that often work well during the squat. Again, I agree with him that phrases like this are usually effective enough that we don’t necessarily need to construct similar type phrases with an external focus.

Finally, Contreras says that he typically uses more internal cues with beginners during the initial instruction period. As the athlete gains experience and expertise, he moves on to more external cues with the idea of getting maximum performance. That process matches what I’ve seen and experienced with my own clients and athletes.

Thoughts

The task for coaches and trainers is to use language to express to an athlete how he or she should move. We may use a description that makes perfect sense to us, yet is completely confusing to the athlete. If that’s the case then we need to pick another description of that movement. Further, a description that’s crystal clear to one athlete may make no sense at all to another. From what the research says, using these external cues is probably the best way to get our athletes and clients to move the way we want them to. We may however need several different external cues to paint the best picture in the athlete’s head. If an internal cue works best then we should use it.

What I’ve learned from reading these articles is that:

- Less is more. Too much coaching confuses the athlete. Fewer/simpler cues are best.

- Directing the athlete’s mind outward will by-and-large get the best performance out of him or her.

- Some degree of internal cueing may be necessary from time to time. We don’t want to throw the baby out with all the internal cueing bathwater.

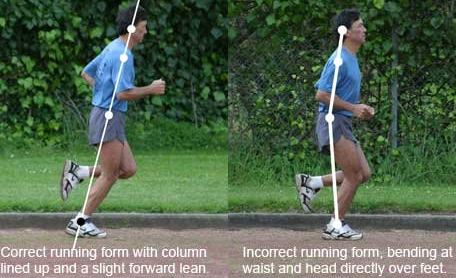

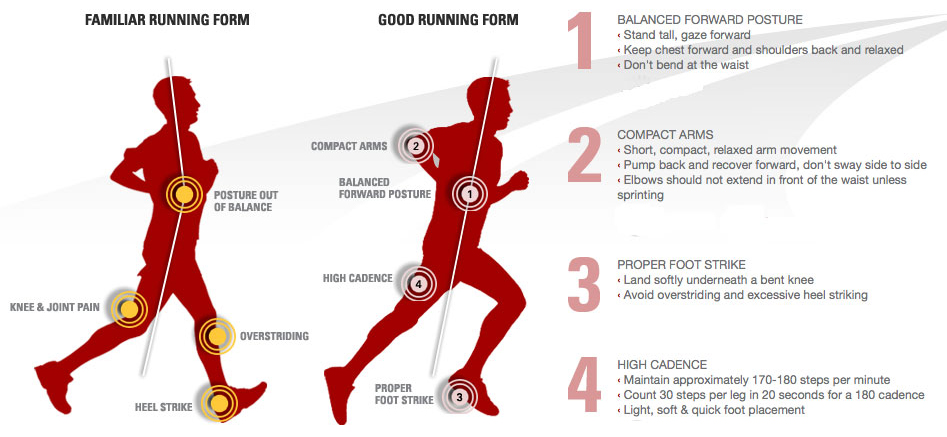

I think we coaches would do well to think of several ways of describing exercises. A good time to do this is during our own workouts. How many ways can we describe moving a barbell or kettlebell? What is important during a push-up and how can we verbalize those points? What are some external cues to describe good running technique? Or weightlifting techniques?

This whole concept of cues is another example example of that the real target with exercise is from the neck up. The brain is the real target here, not the muscles, joints or bones.

ut different” concept. With this concept, we take the main lift we’re working on–the press–and find some way to change it just a little. We offer a little variety to the nervous system, we learn a slightly new skill, and we can improve our main lift.

ut different” concept. With this concept, we take the main lift we’re working on–the press–and find some way to change it just a little. We offer a little variety to the nervous system, we learn a slightly new skill, and we can improve our main lift.