Ouch...

Here is a major drag in my life. I’ve run into injuries off an on over the past few years. Just as I get healthy a new one seems to crop up: back pain, shoulder pain, Achilles tendon pain… The latest and greatest issue is heel pain aka plantar fasciitis. (I’m going to call it PF.)

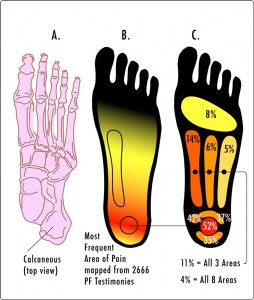

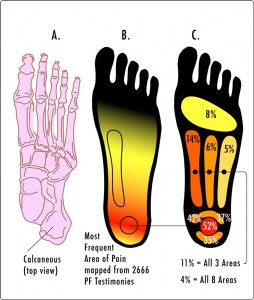

Minor symptoms showed up a few months ago but they sort of came and went. Pain on the outside of my heel wasn’t severe and it faded out rapidly. (I associated plantar fasciitis with pain along the inside of the arch of the foot.) I’d been running some and biking a lot. I’d changed my gait and I was running a good bit in my Vibrams–and I was feeling really good!! (Interestingly, my new gait pattern had helped my Achilles tendon pain. Seems I shifted the stress elsewhere.)

I’ve read up on the issue. What have I found? It seems that one person’s PF is very different from another’s PF. Some runners insist that once they went barefoot, their PF went away. Other runners swear by the opposite end of the spectrum and that orthotics were the cure. Still many many other runners have tried many different treatments but with limited success. Some people suffer with PF for a few weeks or months. Others deal with it for a decade. Much of PF is a big mystery. What’s important here?

Causes of plantar fasciitis:

This is hard to figure out. Like most things involving bodily pain, there’s likely more than one cause. “Improper footwear” is one culprit. Biomechanical glitches such as leg-length discrepancy or tight calves also get blamed, as do high arches, low arches, leg length discrepancy, poor glute firing patterns, tight illiotibital bands. Some sources suggest that PF is due to trigger points, or knots in the muscles. There are many potential culprits for this crime, and most likely some of them are working together.

(I’ll go a little further and suggest that all these issues have causes. If we’re not asking WHY the arches/glutes/IT bands/trigger points are tight/slack/dysfunctional then we’re definitely not getting to the true cause(s) of PF.)

Improper footwear is an interesting issue. Much of the conventional wisdom says we should run in well cushioned shoes that fit our foot type, support our arches and guide our feet properly. Funny thing is military studies such as those discussed in the previous post show that footwear matched to foot type does nothing to decrease running related injuries. Ask barefoot runners and they’ll tell you that any footwear is improper footwear. So what is improper footwear? Seems it’s dependent on the eye of the beholder.

Treatment of Plantar Fasciitis:

Conventional treatment includes rest, ice, anti-inflamatory medication. Orthotics are often prescribed as are calf and foot stretches. Further pharmacological treatment may include a steroid shot. That’s the conventional stuff. What else is there? Well, there are a multitude of therapies and strategies. As I mentioned, it seems that every case of PF is different from every other case. Therefore there are many variations on treatments.

Massage

Rolling a golf ball, lacrosse ball or similar ball along the bottom of the foot helps many PF victims. This is supposed to help break up scar tissue and keep the plantar fascia supple. A similar strategy involves using a foam roller to massage the calf, hamstring, illiotibial (IT) band, glutes, etc. These are forms of self-massage. More formalized massage methods may proove beneficial. Myofascial release, Active Release Therapy (ART), deep tissue massage, trigger point therapy, Structural Integration (aka Rolfing) are examples of massage-type techniques that may prove beneficial in addressing PF.

Shoes

Lots of options here! From barefoot to orthotics and all points in between, what you put on your feet (or possibly take off of your feet) may strongly influence PF. This series of posts on the Runner’s World Forum encapsulates the issue very well. One poster emphasizes wearing orthotics ALL THE TIME, while another poster says, “I think the thing that finally was a breakthrough for me was walking barefoot in the sand.” I’ve found very similar statements throughout my reading. So while there doesn’t seem to be any one shoe-based solution for everyone, consider the idea of changing footwear.

Orthotics are usually expensive. Cheaper options include grocery-store bought arch supports and heel cups. Superfeet and Sole Supports are similar to orthotics but also less expensive.

Joint Mobility/Strengthening

Weakness of the foot muscles may be causing your PF. Therefore, strengthening the foot and lower leg and improving mobility/stability is vital. We may not spend much time thinking about strong feet but hey, we only have to use them all the time every single day right? Maybe it’s actually important! I look to Z-Health R-Phase and I-Phase drills to enhance neural communication and awareness in feet and lower legs. I’ll give some examples.

Start by simply moving the foot and ankle in all available directions. Make circles with your feet. Turn the sole in and out. Flex and extend the toes along with the rest of the foot (make foot waves). Ball-of-foot circles, toe pulls, and knee circles may help as well. You must concentrate and try to make the movements as smooth and refined as possible. Stay relaxed and breathe. Single-leg balance drills may be beneficial too.

My personal opinion is that at some point, barefoot or minimal shoe work should improve foot strength. (Again, some people insist this is the key to their overcoming PF.) It may be too much though if your foot is injured. The plantar fascia may be further damaged if you overload the region. So it may be a progression similar to adding weight to a strength program or mileage to a running program. Start with a small amount of barefoot balance work while still wearing whatever supportive footwear you’ve got. You may gradually add in more barefoot work if the pain decreases. Back off if the pain increases.

Ultrasound, Cold Laser, Shockwave Therapies

Physical therapists and chiropractors often use ultrasound therapy on soft-tissue injuries. The idea is to bring heat to the area and facilitate healing. Research is mixed on effectiveness.

Cold laser therapy is a somewhat new therapy that may aid healing of PF. The evidence is unclear though. Research continues as to what wattage laser is ideal, what wavelength should be used, and how often one should receive treatment. A Runner’s World article profiles one runner’s positive experience with laser therapy.

Extracorporeal shockwave is yet another electromagnetic method of addressing soft-tissue injuries. Similar to ultrasound and cold laser, research is mixed, which shouldn’t be surprising. If we’re dealing with a problem that may have multiple and varied causes it makes sense that one or another type of therapy may or may not be effective. Further, ultrasound, laser and shockwave therapies deal with focused energy. That energy can vary in terms of power and wavelength. An injury may be exposed to varying amounts of energy for varying amounts of time. Thus there are numerous factors that may or may not lead to healing of PF. Lots of choices….

I’ll continue this post with a look at night splints, walking on gravel, magical ceremonies and everything else used to drive out the evil spirit that is Plantar Fasciitis (plus my own strategy in overcoming this issue.)